Upper Highway butterfly and moth biodiversity

Text and photographs Steve Woodhall

Local butterfly biodiversity

The Upper Highway area is extremely rich butterfly-wise. In Kloof alone we have over 200 recorded species. We have several species ‘of conservation concern’ and many local or South African endemics. Before I go into details let’s have a look at why this is.

Why is our butterfly biodiversity so high?

We are fortunate to live in an area with high natural biodiversity because of the varied habitats that exist in our part of the world. We are situated in the Indian Ocean Coastal Belt biome and have a mosaic of Scarp Forest and the endangered vegetation type KwaZulu-Natal Sandstone Sourveld (KZNSS). The latter is often described as grassland yet is categorised as part of the ‘Sub-escarpment Savanna’ bioregion. It’s a mosaic of grassland with typical savanna woody elements. Furthermore, we live in the Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany Hotspot, which is second only to the Cape Floristic Region in Africa, in terms of plant species richness.

We have a varied landscape ranging from low altitude slopes at the bottom of the Molweni Valley at 100m to the high points at Alveston Hill and Monteseel at around 800m. The area is criss-crossed with deep incised forested gorges intimately mixed with gentle grassy slopes.

Butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) are almost all herbivores, and many are single-species or at least plant family specialists. It follows that high plant biodiversity leads to high lepidopteran biodiversity. Because we are in an area that combines subtropical vegetation with some of a more temperate nature (i.e., the grasslands) we probably have more species than somewhere like Cape Town, flagship of the Cape Floristic Region. We have a mix of subtropical elements that might be found further north in Mozambique or Kenya, and specialised ones that have ‘leaked’ into the area from the Cape-type vegetation as Africa’s climate has changed over the eons. Durban has had over 300 species of butterflies recorded since records began to be kept early in the 19th century.

The basis of all this is its geological underpinnings. We live on a low escarpment consisting of Natal Group sandstones over basement granite, with basalt intrusions and a metamorphic zone at the base of the sandstones. Rainfall is high because of proximity to the Indian Ocean and its warm Agulhas Current, so down the eons there has been a lot of erosion and soil creation. Soil types vary from nutrient-poor weathered sandstones on the upper slopes to nutrient-rich valley floors created by weathering of basalt. This means that in an area like Giba Gorge or Krantzkloof Nature Reserve you can move from fire-dominated grassland to thick riverine gallery forest in an hour’s short walk.

Giba Gorge is one of many local nature reserves where you can see grassland and forest butterflies in one short walk. This image shows the KZNSS over Scarp and Riverine Forest.

The gentle slopes between the deep gorges have been used by mankind for millenia. To begin with, Stone Age man hunted there (as can be seen from the tool deposits in places like the Umtamvuna Shelter near Giba Gorge). Then the area became an important cattle grazing resource (Gillitts was home to many early dairies) before the farms were divided into building plots and, increasingly, urbanised in the 20th century. At least one moth species has gone locally extinct because of that urbanisation.

It’s sobering to think what the area used to be like when all those grasslands and savanna were undisturbed. You can get an idea by venturing out to Monteseel where fairly large areas have been preserved.

Relatively large areas of KZNSS are preserved in the suburb of Monteseel.

It is not all bad news, however. As a Metro, Durban has long had an enlightened approach to biodiversity management. The D’MOSS system was set up to provide corridors and refugia for wildlife within the Metro and this has been diligently followed by the Biodiversity Management Department of the eThekwini Municipality. And Kloof Conservancy (and the KZN Conservancies movement) have always stressed the importance of providing suitable habitat. Through education and events like Open Gardens, we have managed to save a lot of suitable habitats in our area. We have a few good stories to tell!

Our local rarities

I think we should be proud that we have at least seven colonies of the Endangered (IUCN Category EN C2a(i)) Yellowish Amakosa Rocksitter, Durbania amakosa flavida, in the Outer West area. The current EOO (Extent of Occupancy) encompasses Amakosa Rocksitter populations in Nkandla and oNgoye nature reserves, which have been identified (at least at Nkandla) as the more widespread Natal Amakosa Rocksitter, Durbania amakosa natalensis. This would further entrench its Endangered status.

One of these colonies is at the Nkonka Trust, where I first saw them nearly 30 years ago. The hillside was disturbed by the laying of a water pipeline, and I feared for their survival, but last December we found them alive and well.

A new colony was discovered at KwaCele, south of Pinetown, by Suncana Bradley during the 2023 Great Southern Bioblitz.

These butterflies are members of the subtribe Durbaniina of the tribe Liptenini of subfamily Poritiinae of the Lycaenidae (Gossamer-winged Butterflies). There are three genera of ‘Rocksitters’ in the subtribe and they are wholly endemic to South Africa. Nothing like them is found anywhere else in the world.

They are found around lichen-covered rocks where they live as larvae on the cyanobacterial component of lichens. The females lay their eggs directly onto the rocks and the larvae graze the lichens, probably ingesting a reasonable amount of rock fragments with them. This would make them ‘ecosystem engineers.’ Over the vast amount of time these butterflies evolved – millions of years – they would have created quite a lot of soil!

A male Yellowish Amakosa Rocksitter at Nkonka Trust, showing his excellent underside camouflage and orange-and-black upperside. These butterflies have aposematic colouration and exude a bitter smelling yellow fluid if molested. It’s not certain how this occurs and might come from the cyanobacterial component of their larval diet. Although this needs further investigation.

A female Yellowish Amakosa Rocksitter on the trail near the Nqutu picnic site in Krantzkloof Nature Reserve – a colony discovered by my Kloof neighbour Mark Liptrot (who has now emigrated to Scotland, sadly). The females are considerably larger and brighter than the males and are easily mistaken for a Painted Lady Vanessa cardui.

A male Natal Amakosa Rocksitter from Mt. Gilboa in the Karkloof, showing his more contrasty underside (less yellow than the Yellowish Amakosa Rocksitter) and larger, redder spots on the hindwing.

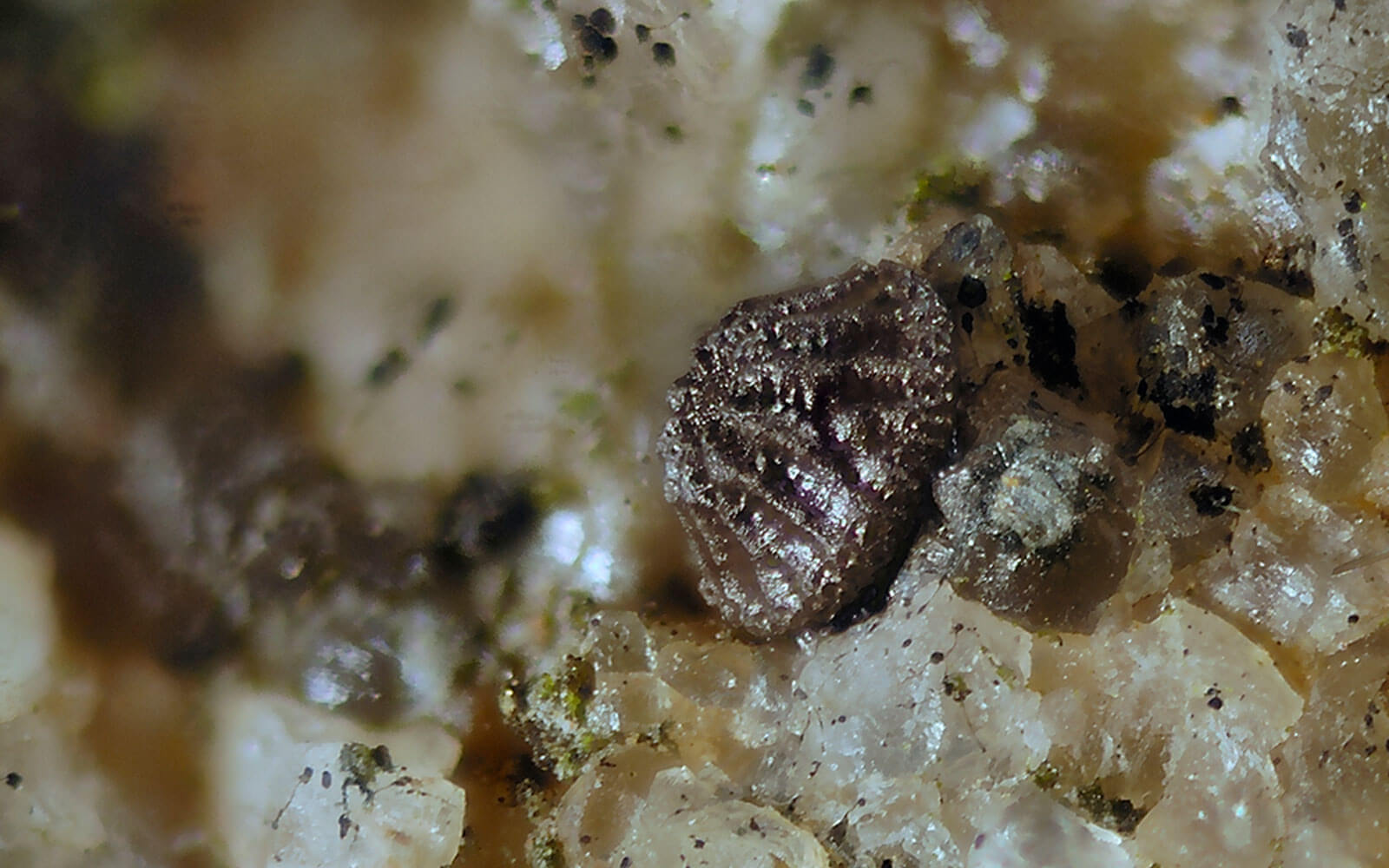

Egg of (IUCN Category VU B1ab(i,ii,iii,iv)) Whitish Amakosa Rocksitter Durbania amakosa albescens from the South Coast. There are in total 7 subspecies of this butterfly found from as far south as Makhanda to the hills of Mpumalanga. Some are widespread but others, like albescens and flavida, are Red Listed. Ours is the rarest of them.

Group of caterpillars of Natal Amakosa Rocksitter found under a rock near Underberg in the Drakensberg. The nutritive value of their food is so low that the caterpillars take a year to develop. They hide under rocks by day and come out to feed at night.

Otto Hirzel (R) and Mark Liptrot at the Durbania spot in Nkonka Trust; Mark is photographing one and the rocks can be seen between him and Otto. The butterflies are shy and reluctant to take wing and are tiny (wingspan 25-35mm).

Males can be spotted perching on the rocks (this takes some practice because of their effective camouflage!) and periodically they fly around the colony in search of the females. The females keep themselves to themselves and seldom take wing. If a male encounters another male a brief territorial battle ensues, with them whirling around one another a few feet above the ground.

The other rare, red listed butterfly found in our area is the Bicolored Paradise Skipper, Abantis bicolor. I have covered this butterfly (and the Rocksitter) before in LE but in a different context.

Bicolored Paradise Skipper is IUCN categorised as Near Threatened (NT B1ab(iii)) and is endemic to the Indian Ocean Coastal Belt biome. It is found from East London in the south to oNgoye and Nkandla in the north. It’s a rare and charismatic butterfly – one of South Africa’s ‘flagship’ species that visitors usually want to see. It can be seen in Krantzkloof Nature Reserve as well as in some of the surrounding suburbs like Forest Hills, in Westville near Palmiet Nature Reserve, and recently atop the Giba Gorge canopy below Mountbatten Place.

They are normally hard to spot because of their rapid flight and habit of keeping to the forest canopy. Occasionally they come to flowers (particularly the females) but this is a rare occurrence. The best way to see one is to go to one of the hilltops in Krantzkloof Nature Reserve and watch the canopy edge for tiny atoms moving like F15 fighters!

Krantzkloof is home to another rare butterfly that isn’t red listed but is normally only found in the cooler Afromontane forests along the Karkloof Escarpment and south to Gqeberha and Knysna. They are uncommon and hard to spot across their range, being canopy insects.

This male of the rare Karkloof Charaxes (or Karkloof Emperor), Charaxes karkloof karkloof, was reared from eggs found on the host plant Cape Redwood Ochna arborea near Nqutu Falls.

Female of Karkloof Charaxes also reared from eggs found near Nqutu Falls.

In 2009 I observed a female Karkloof Charaxes laying eggs on Ochna arborea along the stream above the falls, and in possession of a permit (and having the host plant in my garden) I took them home and reared them to adulthood, photographing all the stages. I released the adults at the place I found the eggs when they emerged from the pupae. This butterfly would probably be missed by most casual observers because (at least in the male) it is very easy to confuse with the common Satyr Charaxes, Charaxes ethalion, whose caterpillars eat the leaves of Flat-crown Albizia adianthifolia and is very common in the area.

The reason why we have such an uncommon and local species in the middle of an urban area is that we have a large well-maintained wilderness in our midst! It’s rather a mystery why they are found at such a low altitude in Kloof compared to the Karkloof. Altitude and latitude are linked climatically – the lower the latitude the higher the altitude. This is why it is found near sea level at Gqeberha but at 1000m in the Karkloof. Its habitat in Krantzkloof is at around 450m.

The egg of the Karkloof Emperor.

The larva (caterpillar) of the Karkloof Emperor.

The pupa (chrysalis) of the Karkloof Emperor.

Now we come to a rather sadder tale. This is about a moth rather than a butterfly. We have several species of Looper moth (Geometridae) whose caterpillars feed on Cycad leaves (much to the ire of some of our gardeners!). Some are common, some are rare.

Some of you might be familiar with the large, spectacular, day-flying Dimorphic Tiger Moth, Callioratis abraxas, a female of which is seen here nectaring on a flowering Umdoni, Syzygium cordatum. They fly in late summer and autumn and like the Bicolored Paradise Skipper are confined to the Indian Ocean Coastal Belt biome. Most people think they are butterflies, but they are actually Loopers from the tribe Diptychini of the subfamily Ennominae of the moth family Geometridae.

For many years, lepidopterists wondered about another large day-flying moth, the related Millar’s Tiger, Callioratis millari. This species’ ‘type locality’ (the place it was first recorded from) was the area around Kloof, Gillitts, and Hillcrest railway stations, but it was last seen there in 1928 – nearly 100 years ago. The habitat in the area would have been modified greatly since that time, rendering it unsuitable for the moth. The insect was feared to be extinct.

Hermann Staude (co-author of the recently published ‘Southern African Moths and their Caterpillars’) refused to believe that it was gone forever. He spent years searching similar habitats to our forest-grassland mosaic and eventually in 1997 found a colony in Entumeni Nature Reserve in Zululand. Its host plant is the Grass Cycad Stangeria eriopus which it uses for the first three instars (moults) of the caterpillar, after which it moves on to secondary angiosperm hosts to complete its larval stage. Amazingly, another population which appears to be this moth has recently been discovered in the Addo Elephant National Park, but it uses a different species of Cycad as larval host – Eastern Cape dwarf cycad Encephalartos caffer.

Male Millar’s Tiger photographed by the author on a visit to the Entumeni locality.

Stangeria eriopus is still found in KZNSS-Scarp Forest mosaics in Kloof. The possibility exists of translocating some material from Entumeni to Kloof, but too little is known about its secondary host plants. In addition, the Entumeni population is under threat from host plant poaching and untimely fires, so it would be difficult to justify such an attempt at this stage.

Such ‘Cycad Moths’ are found in the Eastern African grassland-forest mosaics as far north as Malawi and the Matthews Range in Kenya. But they are always rare. Cycads are ‘among the world’s most threatened organisms, facing critical challenges due to habitat loss, poaching, and reproductive failures caused by the extinctions of pollinators’ according to the authors of a paper published on Callioratis millari (see references). This is why it is so important that suitable habitats be preserved, as they are being in our area.

Every so often, Kloof provides a surprise. Some members of the Lepidopterists’ Society of Africa found some Emperor Moth (Saturniidae) caterpillars feeding on False Assegai Maesa lanceolata in Glenholme Nature Reserve. They initially thought them to be the common Wahlberg’s Emperor, Nudaurelia wahlbergi, but when the moths eventually emerged, they didn’t look like that.

Caterpillar of Variable Emperor Moth, Nudaurelia gueinzii

The beautiful Variable Emperor Moth, Nudaurelia gueinzii, had not been recorded in the Upper Highway area before. It had been found in Zululand and in the Midlands.

Were it not for one of our small local nature reserves, and some eagle-eyed caterpillar rearers, we would not have known this moth occurred here. And that isn’t the only surprise we’ve had.

In April 2023, Mark Liptrot excitedly called me to say he’d spotted a new butterfly for the area in his garden – the Streaked Sailer, Neptis goochii. Apart from a 150-year-old record from Durban it had never been seen around here – it normally never comes south of the Tugela. Then they started turning up in my garden as well – in Gillitts, and then in iPhithi Nature Reserve as well!

Urban development and habitat destruction may seem to be an unavoidable ‘fact of life’ in a modern city, but it need not get to the stage where the original biodiversity disappears. In the Upper Highway area, the preservation of corridors and refugia in the form of parks, nature reserves, and streams and wetlands has shown that we have considerable biodiversity here. Residents can help by planting locally indigenous only, keeping at least part of their gardens ‘wild’, not planting monocultures, and avoiding the use of chemicals, especially harmful insecticides. A well-maintained garden ecosystem will link up with those around you. This will help prevent population explosions of ‘pests’, which are mainly those creatures whose habitat we have replaced with our streets and houses.

References

Staude HS. A revision of the genus Callioratis Felder (Lepidoptera: Geometridae: Diptychinae). Metamorphosis. 2001:12(4):125–156.

Paul Duvel Janse van Rensburg, Hugo Bezuidenhout, Tommie Steyn, Johnnie van den Berg, A new distribution and host record for the rare moth, Callioratis millari (Lepidoptera: Geometridae), and some ecological observations, Environmental Entomology, Volume 53, Issue 2, April 2024, Pages 305–312, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvae008

Steve Woodhall is a butterfly enthusiast and photographer who began watching and collecting butterflies at an early age. He was President of the Lepidopterists’ Society of Africa for eight years, and has contributed to and authored several books, including Field Guide to Butterflies of South Africa and Gardening for Butterflies. His app, Woodhall’s Butterflies of South Africa, is described as the definitive butterfly ID guide for South Africa.

Steve has been a valuable and informative informal guide on many butterfly outings but recently qualified as a formal FGASA Field Guide and is now available to officially guide tours via his ButterflyGear business entity. Steve can be contacted on +27 82 825 8450 or steve@butterflygear.co.za