Tenacity on the environmental frontlines

An interview with Trafford Petterson

Text Paolo Candotti Photographs Trafford Petterson

Safeguarding our biodiversity is not an easy task at the best of times often made more difficult by unnecessary legal complexities, obdurate officials, organisational silos, unrepenting delinquents, physical threats and more than a smidgen of corruption all adding up to a hard day’s work for anyone wishing to take up the challenge. Those willing to enter the purgatory of conservation compliance need more than just a thick skin, they require a degree of tenacity, doggedness and determination that will outdo even the most stubborn criminals! Trafford Petterson (Grade 2 Environmental Management Inspector) has built a solid reputation as a relentless pursuer of anyone stepping on the wrong side of the law when it comes to environmental issues. Through years spent in the field Trafford has realised that not all battles are winnable but once he has made up his mind on an issue he certainly won’t let go!

“Yes, we may lose. But we shall meet them in battle none the less.”

KING THEODEN OF THE ROHAN

Lord of the Rings

Trafford is a true “local lad”, born in Durban, schooled at Kloof High and with a diploma in Nature Conservation, he has been “patrolling” our natural areas from early childhood. Not many youngsters these days would be able to experience our outdoors as Trafford did in his youth.

“I find the outdoors gives me a sense of freedom and belonging I just do not get around crammed humanity. As a child of about 12 or 13 I would come home from school on Friday afternoons and dump all my school books out of my old haversack then fill it again with cans of beans and tinned Vienna’s, an old camp stove and beaten up pan, my Swiss Army knife, say cheers to my folks and go spend the weekend on my own exploring Giba Gorge. I’d sleep in the caves and overhangs in the area and spend the days just wandering about exploring.

During holidays I would spend time on a large family farm outside of Underberg where a strict and formidable uncle would drop me off somewhere with a fishing rod or .22 rifle to spend my day. Most of the time he’d forget to pick me up, so I would walk for miles and hours (sometimes in the cold and rain!) to get back to the farmhouse. I think it was all in the aid of character building!”

Farming in the Kalahari – 1993

The passion for the outdoors, however, did not immediately lead to a career in conservation and sometimes one needs to follow one’s heart as well.

“I’ve done all sorts of things to do with the outdoors. Was a game/cattle farmer, tour guide, game ranger, diamond prospector and even an arms dealer for a short while (all legal, I hasten to add!).”

But the “call” of conservation was eventually one that Trafford could not resist.

“I don’t think there was any single eureka moment, at least if there was, I don’t remember it. It was more of just following a life path that seemed more natural to me. I think I’d always wanted to be a game ranger or at least someone who worked in the outdoors, from when I was small. But as a personal conviction it was when it struck me what people were doing to the land I loved so much that it became personal. If you sit on a rock on your own and stare out over a land that is ancient and pure, it gives you something that no money can even attempt to buy. It gives you inner peace and a sense of being a part of this world not just some transitory being caught up in the crowd. It gives one time to think, time to get to know yourself, instead of an image that has been prepared for you to try and fit into. When that sense of belonging and way of life and way of looking at life is in grave danger of what we like to call progress, it becomes very unsettling. If you feel like that then, naturally, you want to do your bit to try and save what is still left out there. So, conservation is a very personal thing to me. It isn’t just a career path but a vocation and probably what more sentimental people would call a ‘calling in life’.

When in high school I joined their wildlife club and enjoyed the various trips to reserves and other wilder places and then was given as a present a membership to the local Highway Branch of the Wildlife Society (as it was known in those days). So, while other kids of my age were starting to party, I’d be out in the local nature reserves getting to know my plants, cutting endless swaths of invasive weeds and learning many interesting things from the older members. At home I’d devour any book I could find on wildlife and conservation and would spend my time making notes of what I’d seen out there. I still have my old notebooks with line drawings of plants and things.

In a nutshell, I wasn’t totally certain what specific field I wanted to invest a career in, but I did know whatever it was I wanted a lot of outdoor time, preferably as far away from people as I could get!”

Trafford hand rearing an abandoned lion cub – 1999

Asked about individuals who may have influenced his choice of career Trafford was reluctant to name specific individuals but readily acknowledged many “influencers”.

“My uncle up in Underberg had a certain wisdom about him that only an eccentric farmer can have! I remember on one cold berg evening during a chat he said there are times to talk and times to listen. And sometimes if you listen you can learn a lot. In the early days I did a lot of listening. I learned a lot from some, sometimes, quite crusty old folk with a lot of experience in the things I was interested in. I’d listen then try stuff out myself and see if they were right. I think if you show interest in something there are always those who will spend time with you and give you some good pointers. The fastest way to learn nothing is to believe you know everything. So, a little humility and acknowledgement that you are still learning goes a long way.”

The people who influence you are the people who believe in you.

HENRY DRUMMOND

Trafford does not hesitate to acknowledge that “learning from people” is an ongoing process.

“There have been a lot of people who have inspired me along the way. And those who don’t, one can also learn from. Basically, how not to do things! There is also the irony that you also learn not to have heroes. I’ve met some of my heroes and in the flesh and found them to be less than nice people who just happened to market themselves better than others. But inspiration is a strange thing, and it can come from the most unlikely places. It can also come from adversity. In conservation work you can often be faced with some tough situations. Sometimes that is when you really get to know someone and often it isn’t the loud, brash alpha males that come through but the quiet, thoughtful folk who will pull you out of a sticky situation.

When I came down to my current post, folk didn’t really want me around. I was a bit too rough for their image. But my erstwhile “big boss” did give me the latitude to learn many new skills I would not have had the opportunity to have learned if I had stayed strictly in the conservation side of things. Working in an environmental management department is very different to doing reserve work. For one there is a lot of technology and interrelationships one must master that you don’t get exposed to if you are out fixing game fences or burning fire breaks. I’m grateful to those who taught me those skills, directly or indirectly.

On a practical level performing the role of a biodiversity protection officer (the job) and being a conservationist (the passion) at the same time can create dilemmas and personal soul-searching. Trafford was asked how he manages to reconcile these two often conflicting objectives particularly when “compliance” is a complex, time consuming, bureaucratic and often thankless process.

“With great difficulty! In rural districts and in reserves you have the luxury of removing people who are harmful to the environment, arresting them or coming up with home grown ways of dealing with things. In the City or more urban areas there is a different way of doing things, different rules and attitudes. People will try any ploy to remove you from a case, from trying to make you look bad in front of your bosses to going over your head. I once had a particularly obnoxious individual tell my boss in front of me that I spent my working hours getting drunk in local pubs! Luckily, like my boss I don’t imbibe alcohol, and she knew it, but it is still irritating. Folk think because you are a civil servant, they can be particularly uncivil towards you. At times straight enforcement doesn’t work and you must become more creative. Our role is not necessarily to criminalise people. It is meaningless if one manages to put a person in jail and yet the destruction still carries on or the environment is left a mess. For us the ultimate goal is the biodiversity itself. The question is always how do we get a person to stop what they are doing. If people have made an honest mistake and are willing to rectify things we try to work positively with them. But there are many out there who just do not believe in law anymore, sadly.

The other challenge in any compliance role is that we do get lectured to a lot, usually by those who haven’t a clue what they are saying. Environmental law is one thing, and it is fairly specialised, but it is fairly useless if one doesn’t actually know anything about the environment one is dealing with, so we actually do need to know a fair amount about biodiversity, which in itself is specialised.

Part of the Wildlife Society team – from left, Trafford, Ally Ashwell and Terry Stewart – 1991

The carrot and the stick are pervasive and persuasive motivators. But if you treat people like donkeys, they will perform like donkeys

JOHN WHITMORE

Environmental compliance has many facets particularly if in the long-term the goal is for all of society to be willingly to comply on a “duty of care” basis. In this context the question posed to Trafford was “how much of your work is “carrot” and how much is “stick”?

“Biodiversity is a bit different to pollution and waste in that there is not as much scope to be proactive. With the pollution and waste side the authorities will conduct sector inspections or what is known as compliance promotion where they visit factories and educate people or answer their questions and queries on the environmental laws. With biodiversity the damage is usually always done by the time one hears about it and often, even with rehabilitation it can be mostly irreversible. And because it crosses all sectors how does one really dangle a carrot? Who do you target? With pollution and waste, you have a defined target (mostly industry) with biodiversity it can come from anywhere and at any time.

But in my own way I do try and educate as many people as I can out there, and this is where NGO’s become important as ambassadors to spread the word. If we can capacitate organisations like conservancies by understanding the deeper nuances not only of the law but of good conservation practice, then it certainly helps extend the word out there beyond what we can reach. Often residents are hesitant to go directly to the authorities (unless it is to report a neighbour!), so local organisations such as conservancies become their first port of call when they have conservation or nature-based queries. It is thus, in our best interests that those who communities trust to have many of the answers, in fact do have some of these answers or can sometimes act as an introduction to the officials. We aren’t as scary or as stupid as some believe and by a community member saying, “hey, why don’t you ask Trafford, here’s his details” it also helps us engage better with those who do care about their environment.

In my experience there is still a lot of ignorance about the laws, even from those who have amazing biodiversity knowledge. Something I find myself often saying to people, even those I know quite well, is that just because something is environmentally upsetting or repugnant to nature lovers, doesn’t mean it is illegal. I have found many almost have an aversion to even discussing the legalities. They seem to feel somehow it is dirty and tainted. I have spoken to many who are happy to complain but when I explain the legalities they glaze over, and it is obvious they just do not want to hear. Compliance is something that happens out there not in their ambit. It’s a bit like putting the garbage out. It becomes a dustbin persons problem now and folk don’t want anything more to do with it or to think about it. So, it is often much easier to impart biodiversity knowledge to people who are already interested in the topic, but not necessary the laws around it. And I freely admit that that is a generalisation and there are those who are interested. But an interesting general observation I’ve come to notice is that often it is those community members who might not know much about conservation who are more interested than the ‘experts’!”

Durban is blessed with an amazing biodiversity which is the envy of many cities around the world and yet there is a gradual but perceptible deterioration of many environmental standards which may lead the city to being just another “worn out city” in the years to come. Durban (as do most African cities) faces huge challenges with limited resources. Politicians needing to secure their positions mostly prioritise development (couched as sustainable), job creation etc. often at the expense of the environment. How does an environmental officer navigate through these often diametrically opposed forces?

“Not easy at all and a bit of a mine field. Is there such a thing as sustainable development? It’s my opinion that the moment you bulldoze something it is gone forever, particularly if it is a very specialised and delicate system like our primary grasslands. Can we reduce the overall impact? Yes, I believe we can if there is a will to do so. Living an environmentally friendly lifestyle isn’t really an environmental issue. It is a social one. All the science in the world is worth nothing if people have no will to either want to do the right thing or indeed learn what the right thing is. Sadly, we have always been on the outside of commonly accepted governance. Seen as “greenies” and “purists”, whilst engineers, surveyors and town planners are seen as serious professions. So, often it can be an uphill battle to get our voices heard. There are rewards to living environmentally sensitive lifestyles and buying into the ethos as a developer. But they take a bit longer to realise, and people will often err on the side of what produces the quickest and most direct gains. We are a country where there is a massive unemployment inequity so the golden words that seem to open so many doors are “job creation”, “economic growth”, “making the world safer” (things we also generally agree with, if genuine). These are big issues to have to contend with and often we are seen as an irritant before we even walk into a negotiating room, sadly!

The issues are made more complex because much of our urban population has an “out of sight, out of mind” mindset. How do you get people who have never experienced nature to buy into nature? A sad dichotomy is how many people believe that wildlife is something that only belongs in nature reserves and not in any urban setting. Being we deal with all types of people; we sometimes entertain ourselves with the dark humour of what we commonly come across out there (there are definite patterns to how folk react when we visit!). The one that always gets us is those people, often affluent and educated, who, before you have even got out of your vehicle (and usually with absolute environmental mayhem behind them…caused by them…) are regaling you with stories of how wonderful their recent trip to “Kruger” was and how much they love nature! I’ve even had people say as much to me, i.e. that we have enough nature reserves so why are we picking on them and their proposed development!? The other one that boggles the mind is the “out there” attitude. In the old days when I worked in reserves, I’d often field problem animal calls. I’d continually have to ask what the problem was and often, after a lot of waffle like “it runs across my roof in the morning” and such, I’d get “but they don’t belong here”! A very sad attitude to have to constantly have to deal with. Sadly, many wealthy people will settle in peri-rural areas but then bring the “city” with them, which causes a lot of problems, not least of all with locals who have lived in the same area for a long time.

For poorer people just trying to survive, it is also a challenge. We often may hear from dedicated conservation minded people how there is no idea about invasive species or their properties are a mess. But then, if you live in such a desperate space is it really fair to bemoan all the gum trees when there is nothing else around for shade or that they need to think environmentally when just trying to survive is all that is on their minds? There are many contexts, and these things are never straight forward or simple.

All we can really do is work on the education side and try and instil what Aldo Leopold, the American thinker called a “land ethic”. This begins in school, and we really need to see more grass roots projects like the ones WESSA and some of the conservancies get involved in”.

Much local work has been recognised beyond our borders and Trafford was asked his views on how this work impacts on other African cities as well as cities on other continents.

“We have worked with other cities in the past and will continue to do so, but it is also important to recognise that each area comes with its own unique set of issues, and not all are the same. At one stage we did some work with cities around the world, and it was a big eyeopener for those involved in this. Some places in affluent societies just did not get the biodiversity angle at all, possibly because their areas had been transformed so long ago. A funny, but equally sad story was when one of our officials, after giving a presentation on D’MOSS in a European country was proudly taken to an ancient wall in the city and shown a rare species of moss! My point is that biodiversity is a holistic approach to interlocking natural entities and processes. Some parts of the world understand this and some not so much.

I think we are unique in that there is still a lot to nurture to save here, but there is also a need to understand that socio-economic issues are major drivers in the way government views its policies. The reality is that cities round the world are growing exponentially as people leave the countryside in search of better prospects. This places immense strain on biodiversity and the environment. Having wild and natural spaces is often seen as a luxury most cannot afford and those who can, will often not see this point. It is a massive balancing act as cities grapple with finite resources having to stretch them to meet the needs of growing societies.

Looking long term is often seen as a luxury when there are more immediate problems being grappled with such as high unemployment and a need for just basic services. We need to be mindful of this as we just do not have the luxury of saying no to everything we just don’t like.

Durban has made a lot of strides on the environmental side which can be easily overlooked if you are just looking down at your own feet. Environmental protection is enshrined in its IDP and we have dedicated departments and officials to deal with biodiversity that most other municipalities could only dream of having. Many local government structures around the country are struggling with the most basic of services so I believe we are lucky in Durban to have a structure that does focus on that balancing act between environment and services.

Conserve – association of Outerwest conservancies featuring delegates from 10 of the members – circa 2000

Trafford has been “hands on” involved in civil society activities in support of the environment over a very long period so the question was posed on how his civil society involvement helped shape his thinking.

“I worked full time for the old Wildlife Society (WESSA) and got involved with conservancies many years ago (I sat on the original Kloof Conservancy committee under the chairmanship of Lee Gibson) and I spent about a decade on the old KZN Conservancies Association and am a founding member of the national conservancies association (NACSSA). I was also vice chair of the Thousand Hills Tourism board many years ago. So, I’d certainly say I understand civil society involvement and movements and have a little experience in being a part of it. I do believe they are important, otherwise I wouldn’t have given so much of my afterhours time to them! Because of this, I do try and assist them where I can. Having said that, however, when one wears several hats it is vitally important, at the end of the day, to know on who’s time I am operating on at any given occasion. One learns to compartmentalise and sometimes whilst I can fully understand a situation I just may not be in a position to support it officially. This has, however, got easier as our department has embraced working with civil society on several projects where the margins have narrowed a bit more over time.

How it has shaped my thinking is that I am able to see both sides of the “fence”. A sad reality is that government and civil society often see and experience things vastly differently to one another and this creates some angst out there. Both operate very differently and often have very different goals. I often feel it is important to convey these realities to civil society organisations as best I can and find that many people on the outside of government really do want to know where we are coming from and what it is that we do. It makes things vastly easier for government to form working partnerships and collaborations when we can all speak the same language.

A healthy society rests on three pillars: business, government and civil society, or non-profits. Each has a distinct and important role to play, and all three need to work together synergistically to create the most value for society.

JOHN MACKEY

When asked how he perceived the role of civil society in helping him meet his goals Trafford responded.

“Civil society is able to do a lot we cannot do in government and vice versa. The two need to be linked but in order to do so they need to find commonality. Government operates very differently to civil society organisations. For a start, we operate under clear mandates, laws and policies sometimes immoveable or worked out many years in advance. Our role can also be affected by available resources. Whereas civil society organisations set their own goals and policies and have the luxury of a bit more flexibility. Because of this, often the two sectors struggle to understand one another. For any productive working relationship, the two need to understand how each operates and complement each other’s deficiencies or strengths. There can often be a breakdown of trust and relationships because undue expectations crop up. I try hard to explain to people outside of government how we operate and some of the challenges we can face and will often give more information than asked for (unless I am not allowed to speak about something officially) because the more informed the various communities are the easier it is for us to manage expectations. The environmental laws and the departments that regulate them are quite diverse. There isn’t really a one-stop-shop and many in civil society don’t really understand this, so often we will field enquiries or complaints from people who think we can regulate all laws and all environmental issues. There is nothing so dispiriting as to be bashed for not doing something that wasn’t our job to do in the first place! Relationships, however, do help to soften this somewhat. I think we just need to all take the time to listen to each other.

We have seen a lot of encouraging projects stemming from collaborations between government and the private sector and on the environmental side there have been a lot of gains. The Mend-the-Molweni Project in Hillcrest to reduce the amount of fats that restaurants dump into their drains is a good case in point as not only has it reached a considerable number of businesses and made great strides, but by working with the authorities it has also given them (authorities) hope where there was once a lot of despair.

There are challenges all over, and these days this isn’t just a “global south” problem, it is a universal one as the overall global way of doing things is changing. There is a backlash in certain wealthy nations against “being green” and, indeed, some of the desperately needed funding for green initiatives has been cut in a way that will make future environmental endeavours harder to approach. In this milieu it is vital we all work together both civil society as well as government towards protecting what natural capital we still have left. Gone are the days when we fob off these issues as just a government problem. It is all our problem.

One of the reasons why Trafford is well known in the environmental community is because he contributes to environmental initiatives beyond the duties defined by his job description. In his words.

“I try to do little projects here and there that benefit our biodiversity, whether it is an official deliverable or just something I do on the sides or after hours. Compliance work can be very negative as you have people shouting at you all day and can’t always salvage something once it has been totally destroyed, so it helps to balance this out with more positive initiatives. People often use the terms: conservationist, environmentalist, biologist, ecologist, etc. interchangeably, when they are all very different disciplines, albeit with a broad environmental focus. The role of a conservationist is to understand the land and it’s processes as well as the science that the biologists and ecologists provide and come up with workable physical interventions that act in the best interest of what the ambient nature is trying to do. So very hands on rather than theoretical. I see many issues through this conservation lens and this is how I approach things, be they officially or out of the office space and time.”

One little project I have been chipping away at is to try and save 3 rare plant species from extinction using in-vitro cultural methods. A collaboration with our own Parks Department’s Tissue Culture Lab. Often the scientists will flag a species that is critically endangered, but they can sometimes fall short of what one must do to save such species. Usually, the response is that folk like me must just double down on watching these populations and ensuring no one destroys them in situ. This is a very narrow outlook as well as an impractical one too. We are entering an era where we need to become a lot more innovative with how we protect species and populations from extinction. What I have been trying to do is look at ways to save such species, basically in a laboratory, so that wild populations can be replenished. It means we do not leave all our eggs in one basket, so to speak. Some of our species have such low population densities we just cannot take those chances. The species I’ve been working on are so rare there is very little actual information on their biology or ecologies, so the project also gives us the ability to explore some sound assumptions about them. It’s a little project I came up with and pursue and am quite proud to be doing my little bit for species conservation.

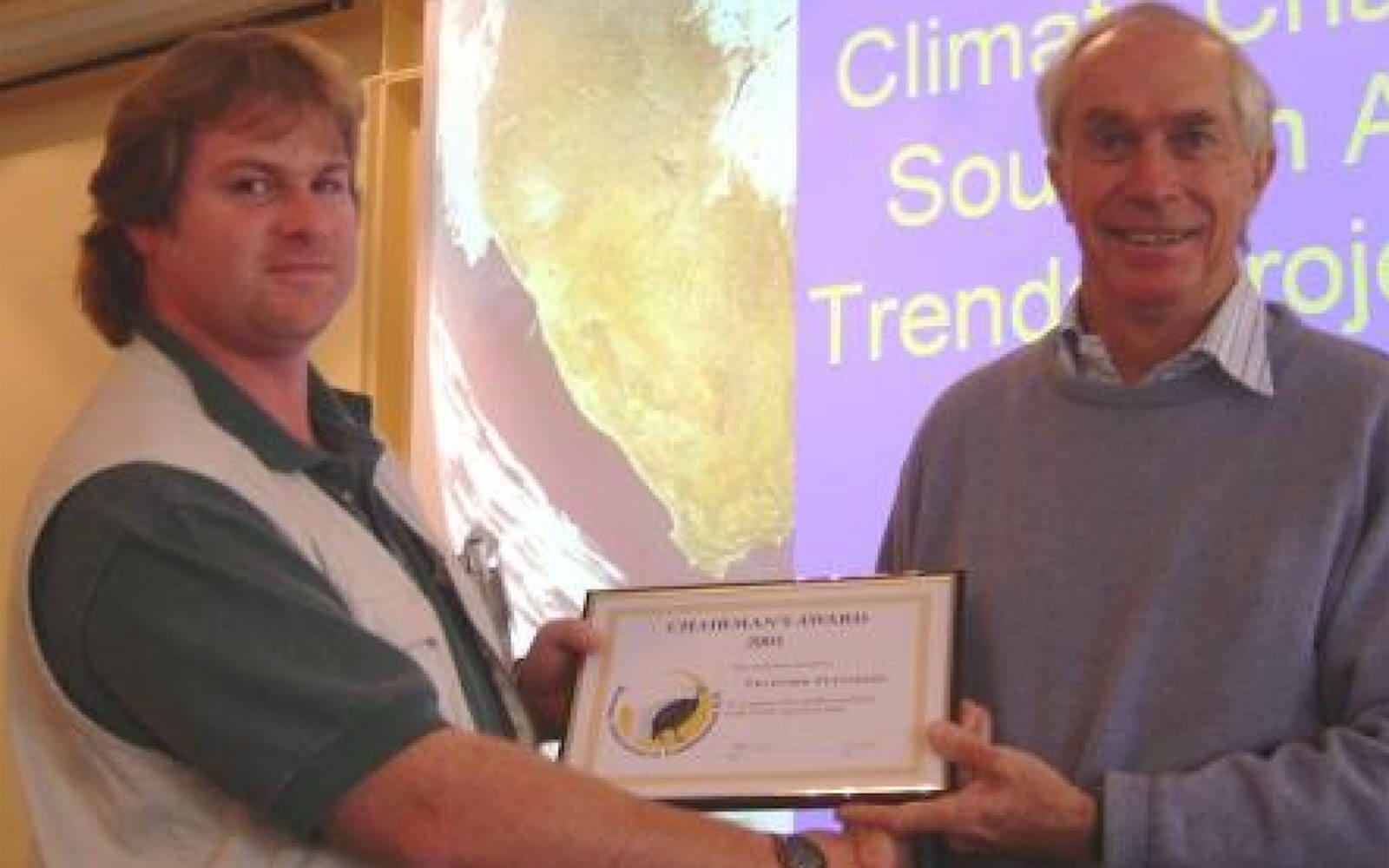

Prof Brian Huntley handing the 2005 Chairman’s Award to Trafford Petterson for his work on the NACSSA Agriculture Policy

I’m also proud of the fact that I was one of the founding members of NACSSA the national conservancies association and that at that time I was involved at a grass roots level when much of the early work on the country’s Stewardship policy was being written. Those were heady days, and I loved the national gatherings where a lot of really good work was being done.

Travel to exotic places is not a condition of employment in the conservation field but occasionally it does happen, and Trafford has had his share of opportunities which he has enjoyed and made the most of.

A few years ago, I was lucky enough to attend one of the IUCN conferences which that year was hosted on a small island in the East China Sea called Jeju and is part of South Korea. I’d never been to the East before, and it was a real eye-opener.

I’ve travelled to some out of the way places in Namibia, Botswana and Lesotho. Again, amazing places to be in. And I do love the Kalahari and desert landscapes. On one occasion I was on a trip through the Skeleton Coast after a very rare rainstorm in the desert and so the going was tough. But an incredible experience.

Representing NACSSA at the 2012 IUCN world conservation congress in Jeju South Korea

Sometimes travel has its risks!

I was walking along the beach outside of Terrace Bay in the Skeleton Coast on my own. Just exploring and enjoying the solitude. There are a lot of whale and seal carcasses and skeletons on this stretch of coast, together with a number of shipwrecks which makes it an appealing place for the amateur explorer. I remember I caught the whiff of something dead and walked up a dune from the beach to have a look, and as I peered over it there was a thin lioness munching away at a “ripe” seal carcass probably about 20 m away. It could have gone badly, but I managed to extricate myself and happily wasn’t eaten that day!

There are also some lighter moments!

“Many years ago, I was taking some folk out on a trail in “big five’ country. It started a bit badly after about half an hour into about an 8-hour hike when we entered a wooded area and all hell broke loose as two old buffalo rammed their way through the forest about 30 m ahead of us. Folk were a tad jumpy after that. But we had a rather exiting follow-up when a white rhino charged the group, fortunately with no consequences for all involved. Back in camp later one of the more nervous chaps came over to me and asked if I would have shot the animal. With a fairly straight face I said something like “geez, never, the paperwork in killing a rhino would be horrendous…it would be easier to shoot you. Besides the gun is just for show…wasn’t loaded anyway!!”. Didn’t go down well. Next morning, I was met by a delegation outside of my tent and forced to load the rifle in front of them!”

Teaching abseiling basics to youngsters in the Drakensberg

As always, our interviews in this series pose a somewhat existential question to our interviewees and this aims at eliciting their views on the general state of the environment, bearing in mind the constant bombardment we all get on climate change, species loss, political inadequacies etc. This may be particularly closely felt by those who, like Trafford are daily on the environmental frontlines!

“We have some very tough fights ahead of us at a global level given that there has been a major paradigm shift amongst some of the wealthy nations of the “global north” which have basically returned us to the environmental dark ages of resource exploitation. This has massive implications both cross border in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, but folk also forget that locally this will also mean massive biodiversity destruction during extraction and the associated pollution that the mining industry really struggles to limit. A hard balancing act and something we ought to bear in mind when we get into our vehicles and fill up our tanks or purchase that latest iPhone!

The climate projections are alarming and yet the world seems very apathetic in moving forward with clear strategies and real time movement on the ground to adapt to the changes we are and will be facing in the future and this is worrying. Somehow, we keep harping on the wrong questions when we deal with climate change. For me we need to put away this constant issue of who started it and rather look at how we are to deal with it.

Spy in the sky – Trafford getting ready to do an aerial compliance survey

So, long term, things do look bleak. But I am always reminded of a passage from The Lord of the Rings. King Theoden of the Rohan is told they are terribly outnumbered. Things look very bleak on the eve of a decisive battle. His advisors say they will lose badly. He turns to them and says, “yes, we may lose. But we shall meet them in battle none the less.” It’s a very powerful and inspirational little movie clip that has always stuck in my mind. You just cannot look at the bigger picture as it appears to us lowly mortals as very bleak indeed. But we all still have the moral obligation to continue to do our bit. We have to. Anything could happen. We must believe in hope, if nothing else!”

Words, thoughts, and actions of a true member of the Eco-Impi1.

Notes

Eco-Impi1

An Impi is defined as “an armed band of Zulu warriors involved in urban or rural conflict”. In our context we refer to an Eco-Impi as those conservationists armed with knowledge and experience who are fighting to help protect our biodiversity and have made a significant impact in our area.