Insects: the silent extinction

Text and photographs Marlies Craig or as credited

The focus of this edition is ‘endangered species’. This is a good opportunity to share the third instalment on the temporary insect exhibition, which went up at the Durban Natural Science Museum back during the COVID pandemic. It was entitled, “Insects: the silent extinction”.

The first two articles covered some important roles that insects play in nature: pollination, seed dispersal, recycling and improving soil quality, pest control, weed control, and population control. This article presents the contents of the third display case at the museum, which focussed on the ‘extinction’ aspect.

But first, I would like to introduce a group of insects that are particularly endangered in this modern world of industrial scale agriculture, pollution, environmental degradation and climate change: mayflies.

Mayflies

Order Ephemeroptera is an ancient group, the most primitive of flying insects, and one of three primitive orders of insects with aquatic nymphs – the other two being Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies), and Plecoptera (stoneflies).

Mayflies spend almost their entire lives underwater as nymphs (called ‘naiads’), feeding on algae. Naiads are easy to find in clean water, in dams and streams, from the Drakensberg down to the coast. They also occur around eThekwini municipality. Pick up a stone from the stream bed and turn it over – the naiads will be scuttling along the rock surface.

Mayfly naiads in a shallow sandy stream, South Coast near Bazley Beach.

Some species take several years to grow up. But at last, in spring, or even on a particular day measured by the full moon, millions and billions of them emerge at the same time. Mayflies are called ‘one-day-flies’ in many languages, since adults survive only a few hours, even as little as 5 minutes, and at most a day or two. Since mayflies are so short-lived, they must all emerge together, else they would miss each other. Those that emerge at another time are unlikely to reproduce. They have no time to eat, and no mouthparts to eat with. All they do, before they die, is swarm and mate.

After mating, females lay thousands of eggs on or in water. In some species the egg-loaded females simply fall into the water exhausted and drown. Their bodies burst open, the eggs spill out and sink to the bottom. Job accomplished.

Mayfly adult male spotted in my garden in upper Pinetown.

Male mayfly spotted in Royal Natal National Park.

Male mayflies can be identified by their strange, divided eyes, mentioned in a previous article.

Mayflies are unique in that the adults, once emerged from the nymphal skin, moult again – wings and all. This photo shows a first adult (subimago), and the empty skin of another.

This mayfly swarm emerged on a warm early spring evening on 25 August, in the Baynesfield area, at a farm dam with very clean water.

Millions of drowned mayflies dot the water, a feast for fish, birds and dragonflies.

Mayflies are keystone species, critical to other species in the ecosystem. If they were to disappear, it would have devastating and cascading effects on consumers throughout the food web. They are a key food source for freshwater fish. Swarms of mayflies also transport tons of nutrients out of the water, into the air, for birds and bats to eat, thus carried far afield, fertilising the surrounding countryside. In the great lakes area of North America swarms of up to 80 billion individuals have been recorded, so massive they are visible on weather radar, and later scooped up with snowploughs.

Sadly, mayfly populations have been plummeting, due to a combination of factors. The first is the wide-spread use of insecticides. Neonicotinoids, a widely used class of insecticides, are highly toxic to the insects, causing death even at low concentrations. Neonicotinoids persist in the soil and are easily blown around by the wind, contaminating nearby waterways.

Water pollution with agricultural fertilisers result in harmful algal blooms, which reduce oxygen levels and release toxic byproducts. An increase in water temperature due to global warming affects mayfly development and reduces water mixing, starving the bottom-dwelling mayfly nymphs of oxygen. In fact, mayflies are known as an ‘indicator species’, a natural barometer of water quality.

After this introduction, let’s now turn to the content of the exhibition.

A world without bees

Every year during the month of February, millions of almond trees begin to bloom in an expense of more than 800,000 acres stretching from Sacramento to Los Angeles in the USA. 31 billion honeybees are required to pollinate these flowers which will ultimately result in 700 billion almonds!

Where do these bees come from? They are brought in by around 1600 of the nation’s beekeepers riding inside more than one million boxes loaded onto thousands of tractor trailers. These bees are also used in the pollination of numerous crops around the USA such as cranberries, blueberries, apples, cherries, pumpkins, sunflowers, clover, squashes, etc.

Now, however, a mysterious bee killer is causing the death of innumerable honeybee colonies, mostly in North America and Europe.

This so-called ‘colony collapse disorder’ (CCD) is such a severe threat to agriculture, and with it the human food supply, that it is making major headlines. What is causing CCD? Is it a parasite, fungus, virus or bacterial disease? Are the bees being poisoned by insecticides used in agriculture? No one is a hundred percent sure. What we do know is that it is getting worse.

In China, things have gotten so bad that the local bee populations have completely disappeared. Farmers now have to pollinate by hand!

What is happening to our insects?

It’s known as the windscreen phenomenon. When you stop your car after a drive, there seem to be far fewer squashed insects than there used to be.

Scientists have long suspected that insects are in dramatic decline, but new evidence confirms this. This past year we have had some very disturbing reports from Europe – over the last 25 years 80% of insects have disappeared. This is very, very bad news because insects are very important in this world.

Pollinators, which are necessary for 75% of food crops, are declining globally in both abundance and diversity. Bees, in particular, are thought to be necessary for the fertilisation of up to 90% of the world’s 107 most important human food crops.

The decline in bee numbers has attracted much public attention. Members of the British Beekeepers’ Association have issued numerous warnings that in the 21st century the country’s bees are in rapid decline. Writing in 2013, Elizabeth Grossman noted that the winter losses of beehives had increased in recent years in Europe and the United States, with a hive failure rate up to 50%. In France, the honey harvest for 2017 has been estimated at around 10 000 tons, representing a decline of two-thirds against the average annual harvest during the 1990s.

A 2017 study led by Radboud University’s Hans de Kroon, using 1500 samples from 63 sites, indicated that the biomass of insect life in Germany had declined by three-quarters in the previous 25 years. Participating researcher Dave Goulson of Sussex University stated that their study suggested that humans are making large parts of the planet uninhabitable for wildlife. Goulson characterized the situation as an approaching “ecological Armageddon”, adding that “if we lose the insects then everything is going to collapse”. Lynn Dicks at the University of East Anglia in 2017 estimated the rate of decline in flying insect biomass at roughly 6% a year.

Cuckoo wasps are dependent on other bees and wasps, whose brood they parasitise. If the hosts disappear, so will these beautiful animals.

What is causing the decline?

Probable explanations for the decline in pollinators can be attributed to the use of pesticides, pests and diseases, habitat destruction, air pollution, climate change, the effects of monoculture (especially in regards to bees), and the intraspecific competition and interspecific competition between “native and introduced or invasive species”.

Pesticide use

Studies have linked neonicotinoid pesticide exposure to bee health decline. These studies add to a growing body of scientific literature and strengthen the case for removing pesticides toxic to bees from the market. Pesticides interfere with honeybee brains, affecting their ability to navigate. Pesticides prevent bumble bees from collecting enough food to produce new queens.

Pests and diseases

Increased international commerce has moved diseases of the honeybee such as American foulbrood and chalkbrood, and parasites such as varroa mites, acarina mites, and the small African hive beetle to new areas of the world, causing much loss of bees in the areas where they do not have much resistance to these pests. Imported fire ants have decimated ground-nesting bees in wide areas of the southern US.

Loss of habitat and forage

Bees and other pollinators face a higher risk of extinction due to loss of habitat and access to natural food sources. The global dependency on livestock and agriculture has rendered no less than 50% of the earth’s landmass uninhabitable for bees. The agricultural practice of planting one crop (monoculture) in a given area, year after year, leads to extreme malnourishment.

Air pollution

Researchers at the University of Virginia have discovered that air pollution from automobiles and power plants has been inhibiting the ability of pollinators such as bees and butterflies to find the fragrances of flowers. Pollutants such as ozone, hydroxyl, and nitrate radicals bond quickly with volatile scent molecules of flowers, which consequently travel shorter distances intact. There results a vicious cycle in which pollinators travel increasingly longer distances to find flowers providing them nectar, and flowers receive inadequate pollination to reproduce and diversify.

Changes in seasonal behaviour due to global warming

Back in 2014, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reported that bees, butterflies, and other pollinators faced increased risk of extinction because of global warming due to alterations in the seasonal behaviour of species. Climate change was causing bees to emerge at different times in the year when flowering plants were not available.

What are the consequences?

Plummeting insect numbers ‘threaten collapse of nature’.

The world’s insects are hurtling down the path to extinction, threatening a “catastrophic collapse of nature’s ecosystems”, according to the first global scientific review. The new analysis selected the 73 best studies done to date to assess the insect decline most of these were done in Western Europe and the US with a few ranging from Australia to China and Brazil to South Africa.

More than 40% of insect species are declining and 1/3 are endangered, the analysis found. The rate of extinction is 8 times faster than that of mammals, birds and reptiles. The total mass of insects is falling by a precipitous 2.5% a year, according to the best data available, suggesting they could vanish within a century.

One of the biggest impacts of insect loss is on the many birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish that eat insects. “If this food source is taken away, all these animals will starve to death.”

Such cascading effects have already been seen in the El Yunque National Forest Reserve, a protected rainforest in Puerto Rico, where a recent study revealed a 98% decline in ground insects over 35 years. “The most likely culprit by far is global warming… The number of hot spells, temperatures above 29°C, have increased .. from zero in the 1970s up to something like 44%” of days in the year.

Another study from Germany reported that over the last 25 years 3/4 of insects have disappeared and a study in Scotland showed a 2/3 drop in insects between 1970 and 2002.

The Puerto Rican Tody, which eats insects almost exclusively, diminished by 90%.

Photo: Dick Daniels

The biomes of Anole lizards, which feed on arthropods, dropped by more than 30% from the 1970s. Some species have disappeared completely.

Photo: Tkennedy239

Crop pests will increase while beneficial insects will die off

Insects that are likely to benefit from global warming are crop pests. Crop losses for critical food grains such as rice, maize and wheat, will increase substantially as the climate warms. Rising temperatures increase the metabolic rate and population growth of insect pests, especially in temperate regions.

There are approximately 250,000 species of flowering plants that require animal pollinators, the vast majority of these being insects. A third of the world’s crops, including most fruits, rely on insect pollination. Insects play a key role in digesting dead and decaying animal and plant material, and are indispensable in maintaining soil quality.

Fall army worm.

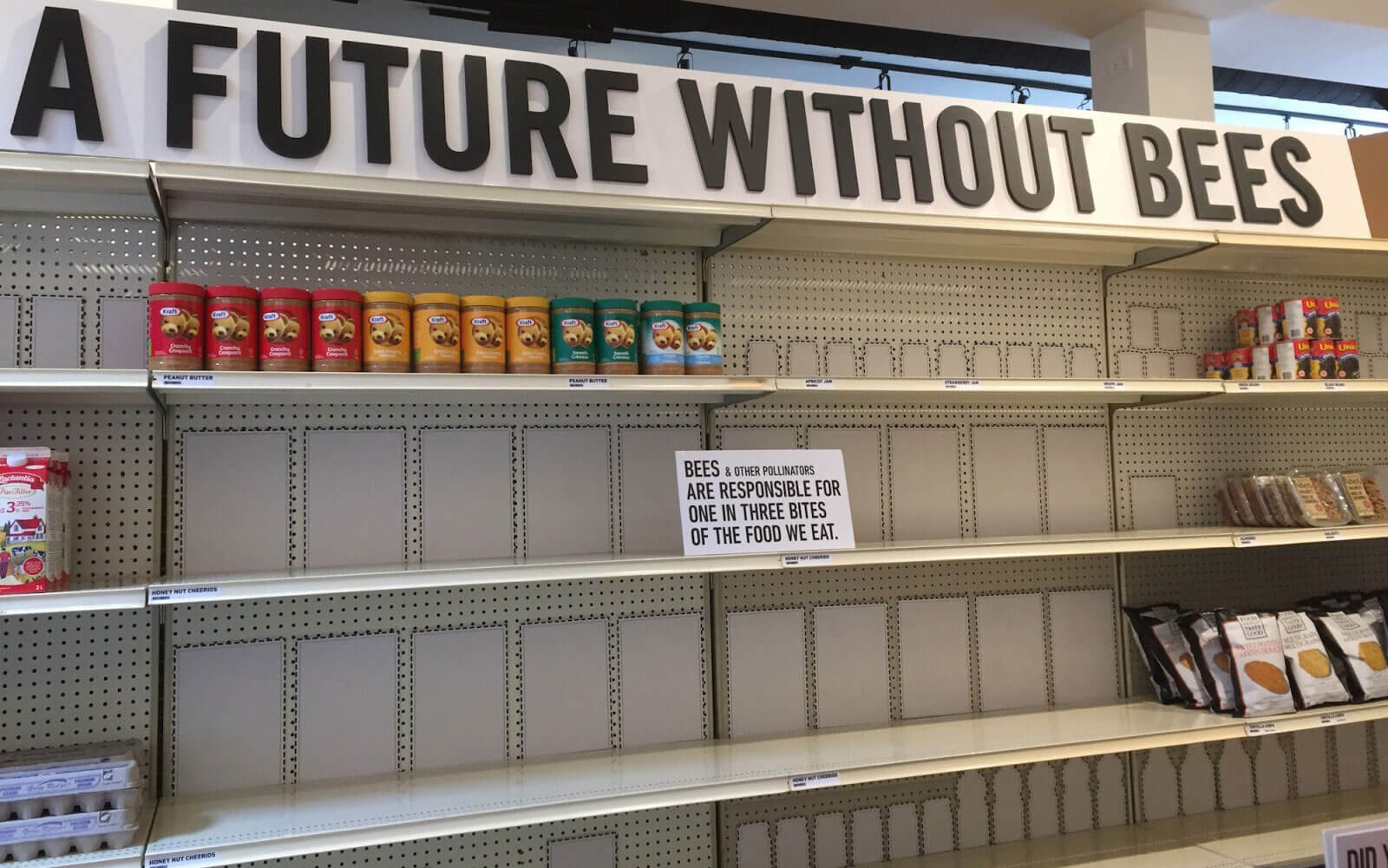

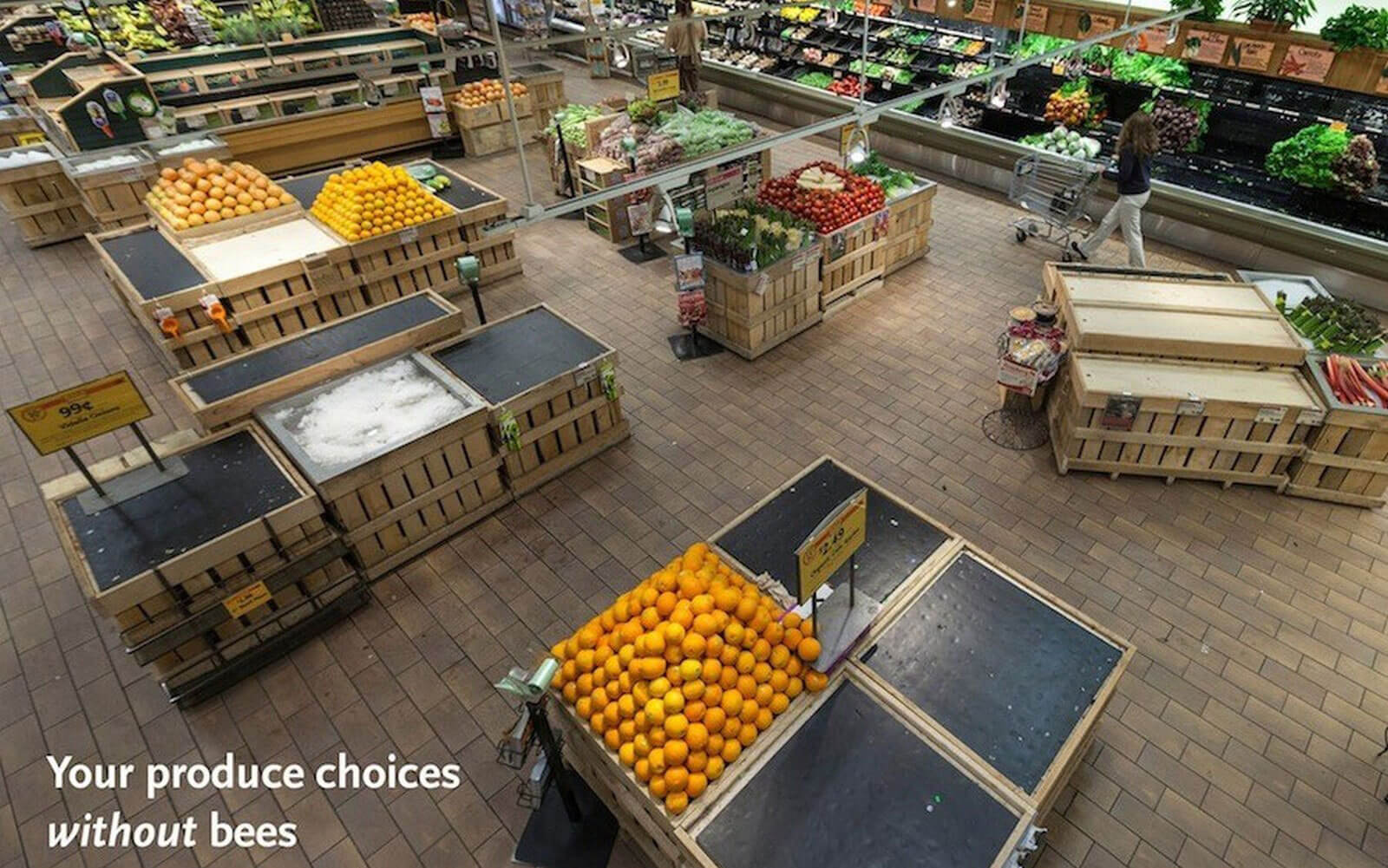

Where did all our food go?

Various supermarkets removed all of the fruits and vegetables dependent on pollinators from their produce section to create a striking visual of what supermarkets would look like without these important creatures. One store ditched a shocking 237 items, or 52 percent of the normal product mix. These included: apples, onions, avocados, carrots, mangoes, lemons, limes, cucumbers, cauliflower, leeks, etc. In addition, the dairy counter would be bare. Milk, yogurt, butter and cheese would disappear.

Your future with pollinating insects

Your future without pollinating insects

Conclusion

I hate to end on such a depressing note. The insect exhibition contained one more important section, ending on an action point: what can we do, to help insects? But as this article is already quite long, that will have to wait till next time.

About the author

Marlies Craig is an epidemiologist by training. She has worked for the Medical Research Council, then more recently for the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and is now employed at the WITS Reproductive Health Institute in the Climate Change and Health unit. Though she did originally study Biology and Entomology, her love affair with insects is very personal. In her book What Insect Are You? – Entomology for Everyone, she shares that passion with young and old, see What Insect Are You?. She hopes to kindle in people of all ages enthusiasm and a deeper appreciation of nature and show them why and how they can make a difference. She also started a non-profit organisation called EASTER Action which hopes to promote awareness and action on biodiversity, climate change, and sustainable living, see EASTERaction.org.

About Andrew Carter

Andrew Carter worked as Museum Officer at eThekwini Municipality for 34 years and during this time he put together many of the displays at the Durban Natural Science Museum, including this one on the disappearance of insects.