Insects? Nature? It’s all about plants!

Text and photographs Marlies Craig or as credited

With arbour week coming up, this is the perfect time to share the fourth and final instalment on the temporary insect exhibition, which went up at the Durban Natural Science Museum back during the COVID pandemic.

The message is (spoiler alert): It’s all about plants!

The first two articles covered the important roles that insects play in nature: pollination, seed dispersal, recycling and improving soil quality, pest control, weed control, and population control. The third article discussed the global decline of insects, and how this impacts our food system.

This last article will cover the last major role of insects: being food for others. Then we ask: if insects are so important for the survival of nature as a whole, what do insects need to survive? How important are insects in nature, as a sum total of all the roles they play? And what is our role in all of this?

Insect role 8: Getting Eaten

First of all, who or what eats insects? How many animals depend on insects for food?

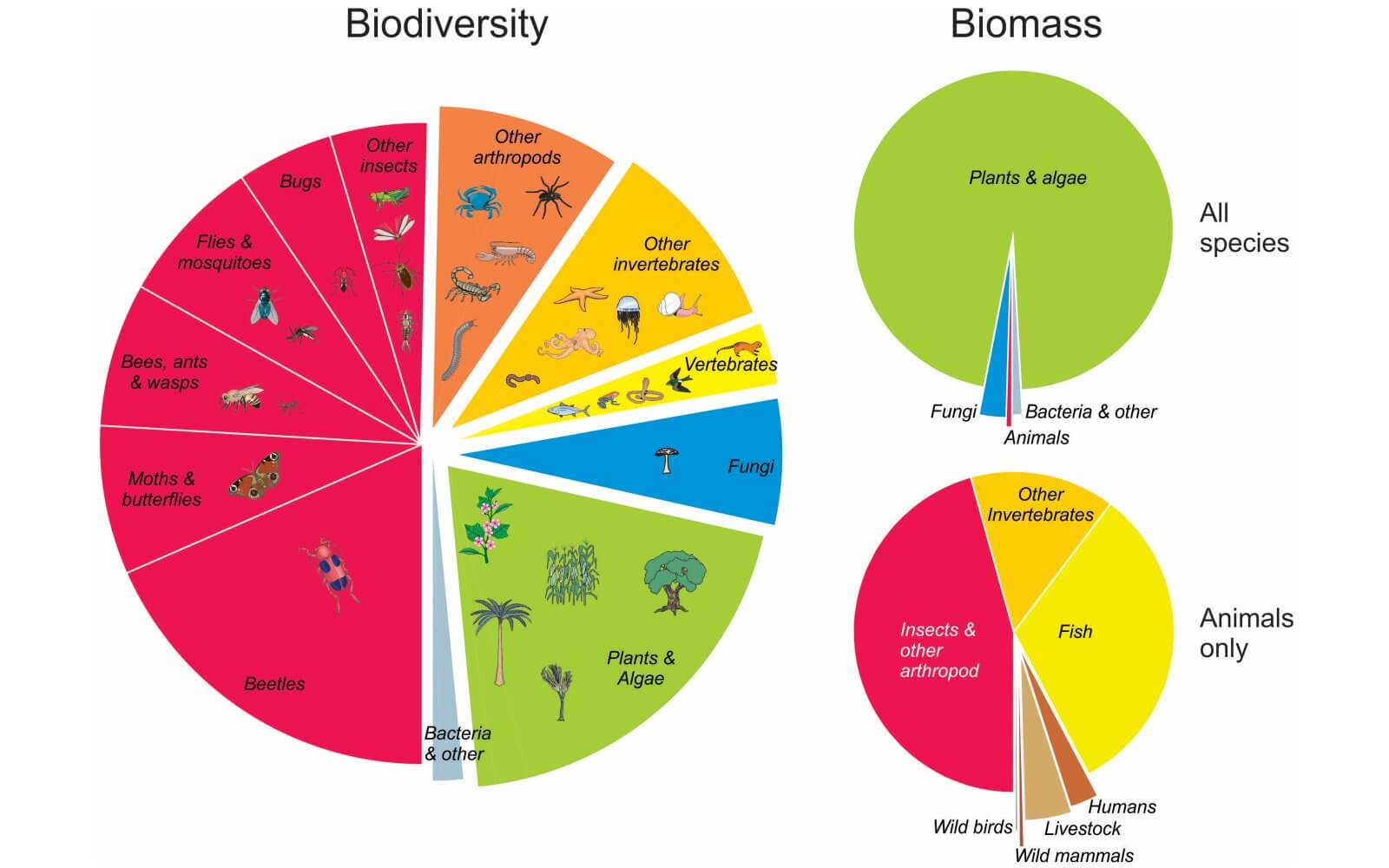

The food web in nature (which we are part of) is determined by the biodiversity of species (how many kinds of living things are out there and who eats what), and biomass (how much is there of everything, by weight).

This is a simple illustrative food web. Mouse eats maize. Cat eats mouse. Cat also eats grasshopper and grasshopper also eats maize. Bird eats grasshopper and cat eats bird. Flea bites cat. Flea also bites mouse. And so on.

But in nature we are not talking about fifteen species, as in the illustration, we are talking about a million species – or several million, who knows how many, there could be five or ten million – depending who you ask.

Insects represent over half of all known species on the Earth, which should give us an inkling of how vital they are in the workings of nature. Insects also make up a massive part of total animal biomass.

Each species has thousands, millions, billions or trillions of individual members! All these trillions of individuals and millions of species are interacting in an unimaginably complex web of interconnectedness.

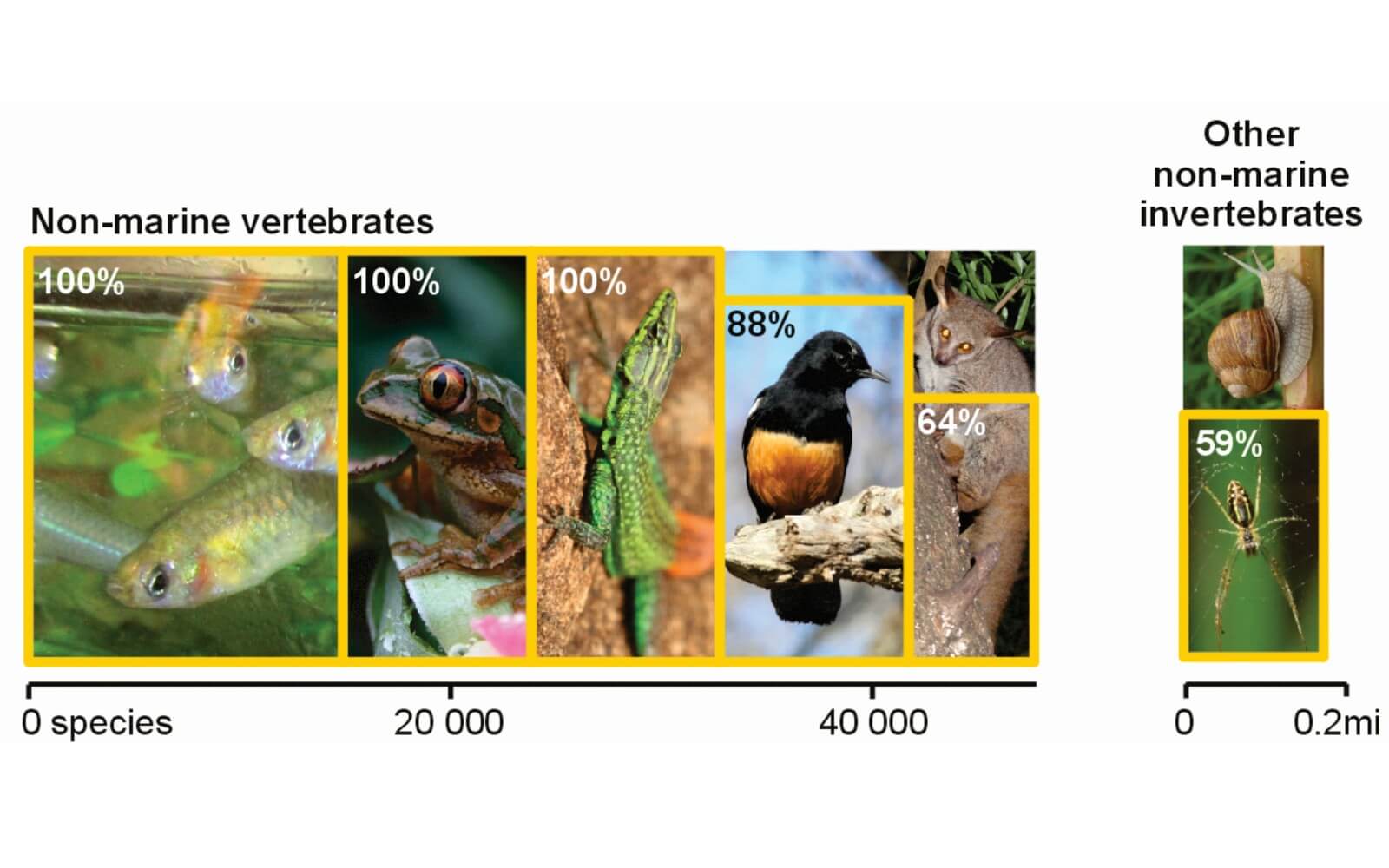

Let’s go through the animal groups one by one, starting with fish:

Fish are not fussy and eat whatever is available. Since 99% of food of a certain size is aquatic insects, freshwater fish are almost guaranteed to eat insects at some stage during their life, even if they grow into predators or herbivores as adults.

Nearly all reptiles eat insects, at least as juveniles, even baby crocodiles.

All amphibians eat insects: frogs, caecilians, and salamanders.

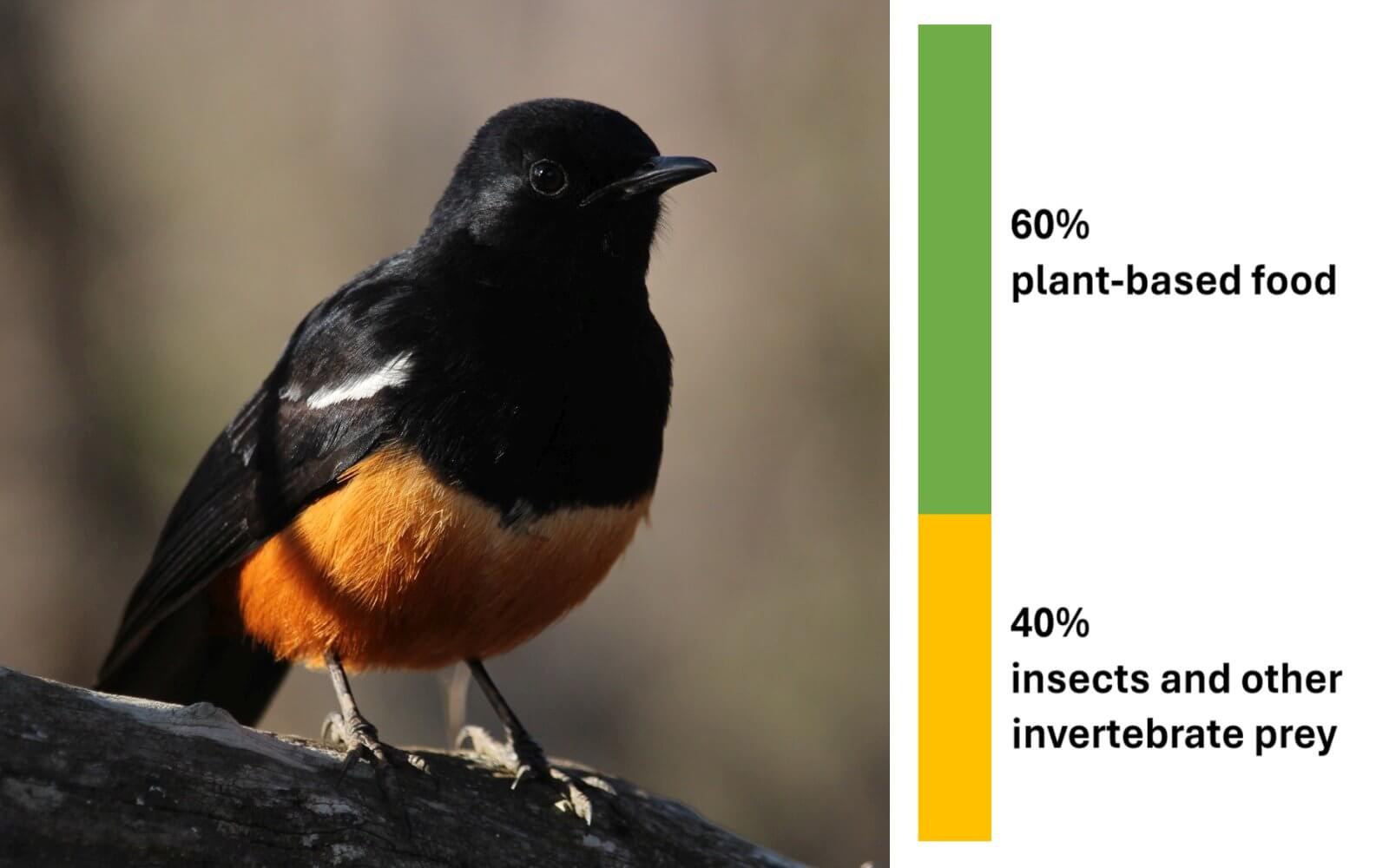

Birds often have mixed diets. Many species are ‘generalists’ which means they eat a variety of foods, such as fruit, seeds, nectar, small vertebrates and other invertebrates, however insects form an important part of their diets. Just how important?

The mocking cliff chat for example (bird #9393 in the global bird list) has a diet of 40% invertebrate prey (mostly insects) and 60% plant based (40% fruit and 20% nectar).

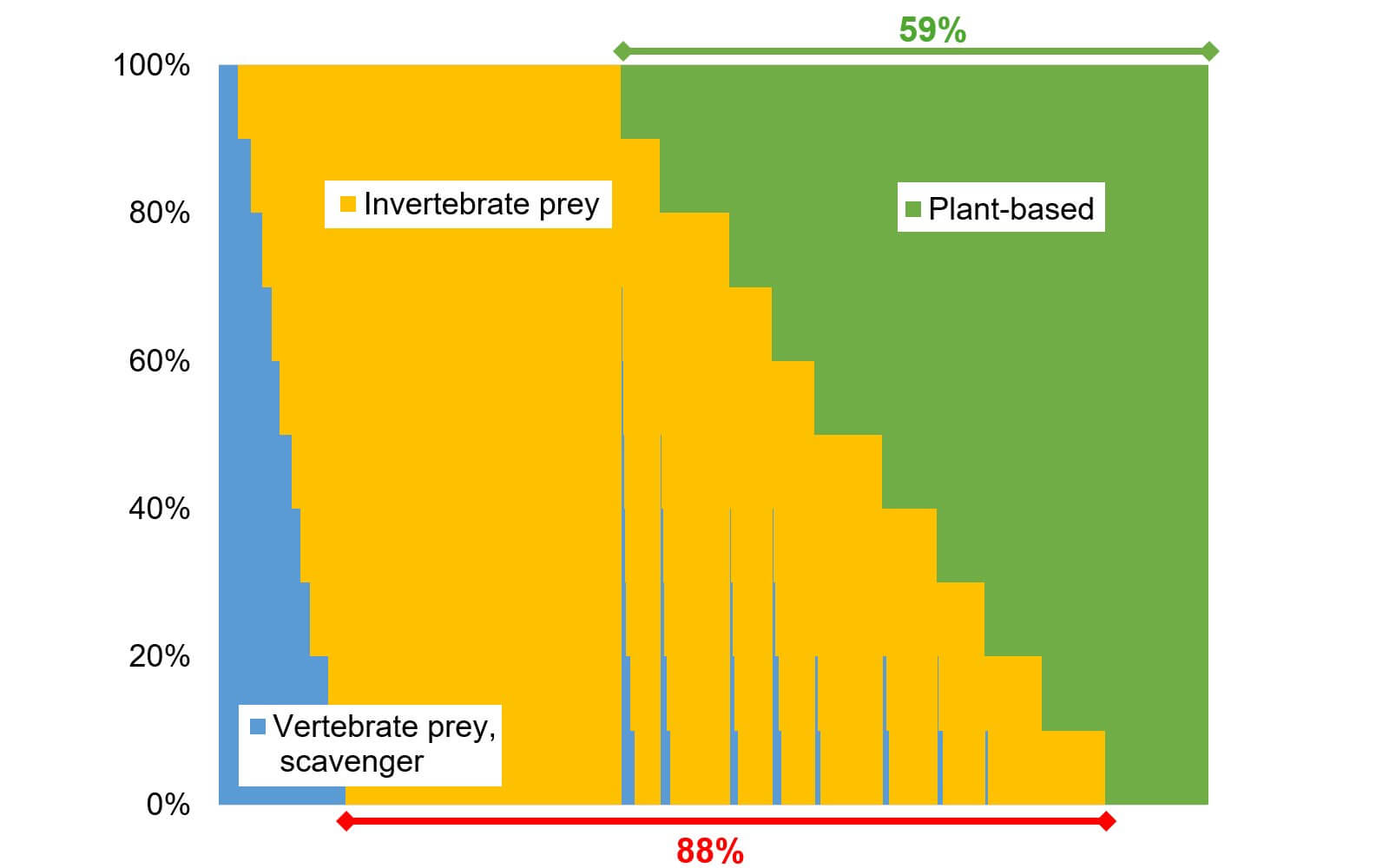

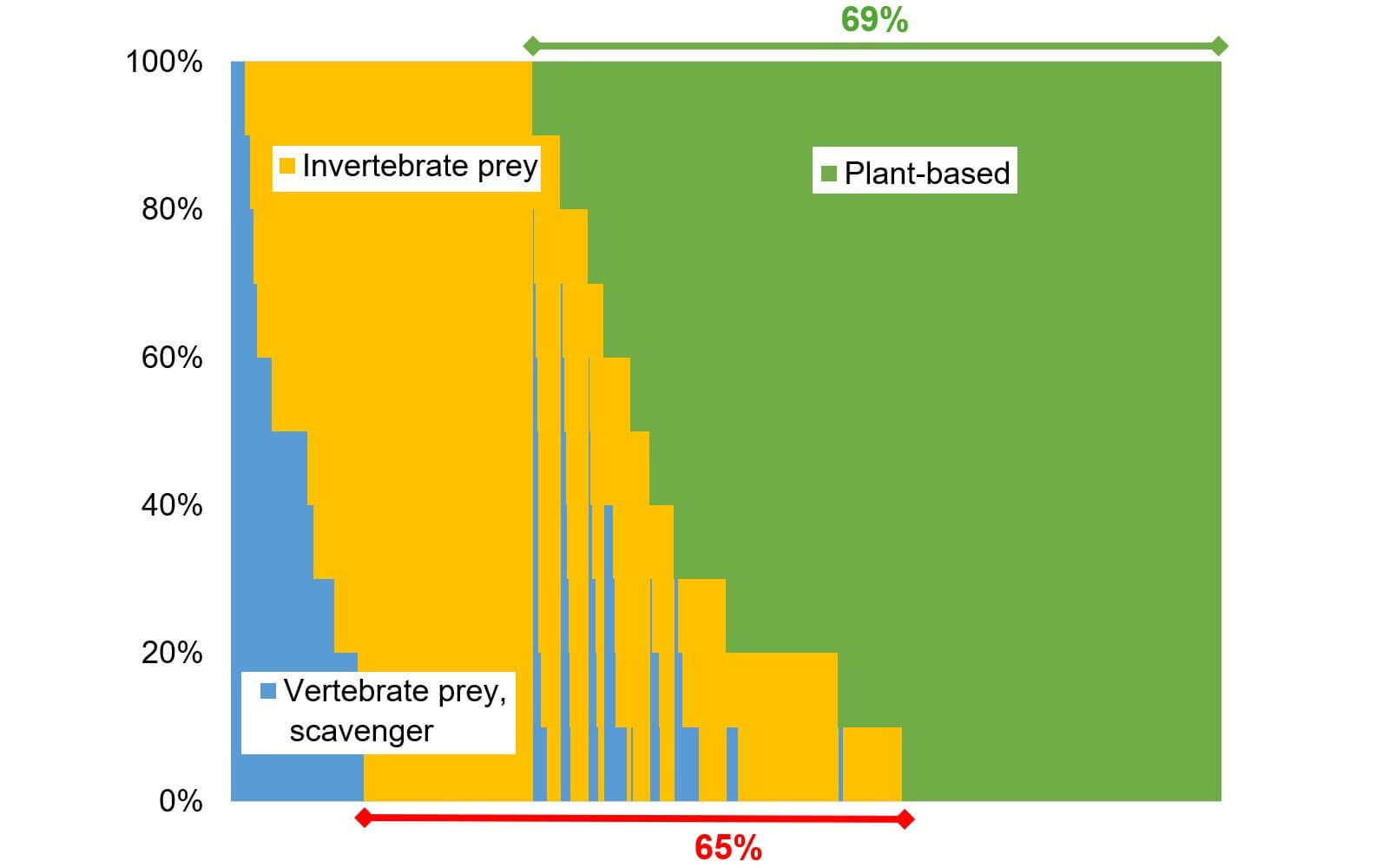

This is what the diet profile of all 9993 bird species of the world looks like, if we stack individual diets side by side, in tight columns.

Amazingly, 88% of bird species eat insects, at least some of the time, while 59% have diets that contain plant matter of some sort (e.g. fruit, seeds, nectar).

Mammals as a group, also have rather mixed diets.

For example, the diet of the brown greater bushbaby is reported being 20% insects and other invertebrates, 20% fruit an 60% nectar.

The diet profiles of all 5400 mammal species worldwide, when stacked together, show that 69% eat plants, and 65% (two thirds!) eat insects, at least some of the time.

Not only vertebrates, but invertebrates too, feed on insects: around 59% of non-insect invertebrate species have insects in their diet. Plus around 25% of insects eat other insects.

Most land chelicerates (e.g. all spiders, scorpions, sunspiders, whipscorpions, whipspiders, daddy-long-legs, and around a third of mites) all feed on insects.

Centipedes also prey on insects.

Terrestrial invertebrate groups that mostly do not eat insects, include snails, centipedes, crabs, earthworms.

Animals need insects

To summarise: on land, 94% of vertebrates and 59% of invertebrates, eat insects directly. On top of this, about 25% of insect species eat other insects. Any predators of these animals, would therefore depend on insects for food indirectly.

The size of the boxes shows how many species are in each group. The yellow shows how many eat insects directly. (Note that invertebrates have a different X-axis, with .2 million – or 200 000 species, compared to under 50 000 vertebrate species)

So, without insects, all these species would starve. The food web on land would collapse.

But that’s not all.

Plants need insects

As we know, plants are the primary producers in nature, and everyone ultimately needs plants to survive – first the herbivores, next the carnivores that eat or nibble on the herbivores, and finally the scavengers or detritivores that eat everything that is dead.

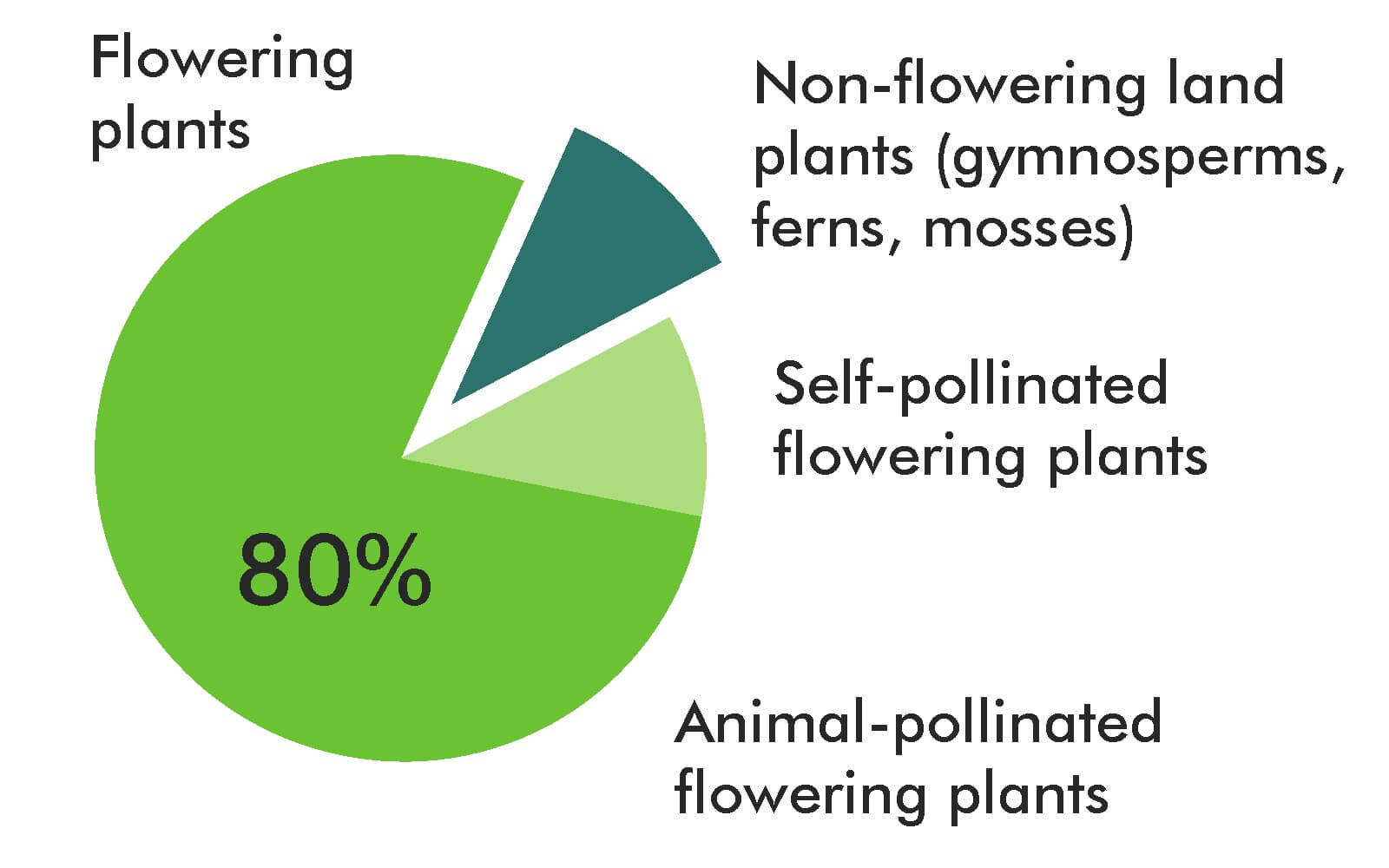

We also know that many plants need insects to pollinate their flowers. But… how many plants exactly?

Of land plants, 91% are angiosperms (flowering plants), and 88% of these require pollination from animals. They are mostly pollinated by insects, but also sometimes by bats, birds and small mammals (each of which need insects in their diets to survive, remember).

So 80% of land plants need insects to survive, and therefore animals that feed on these plants – exclusively or partially – also depend on insects for their survival, indirectly.

And do you remember insect role 2 – seed dispersal? Ensuring the survival of 20% of plant species in the Cape Fynbos biome for example?

So, if most plants and animals need insects to survive, should we not ask, what do insects need? What do insects eat, exactly? What is needed to keep the entire food web going?

Insects need plants

As we have seen, insects are a major link in the food chain – eating all kinds of things, eating each other and getting eaten by others.

Some insects of course eat plants. These insect herbivores must be an even more fundamental link in the food chain – connecting the producers (plants) with higher trophic levels (other animals), while supporting plant survival.

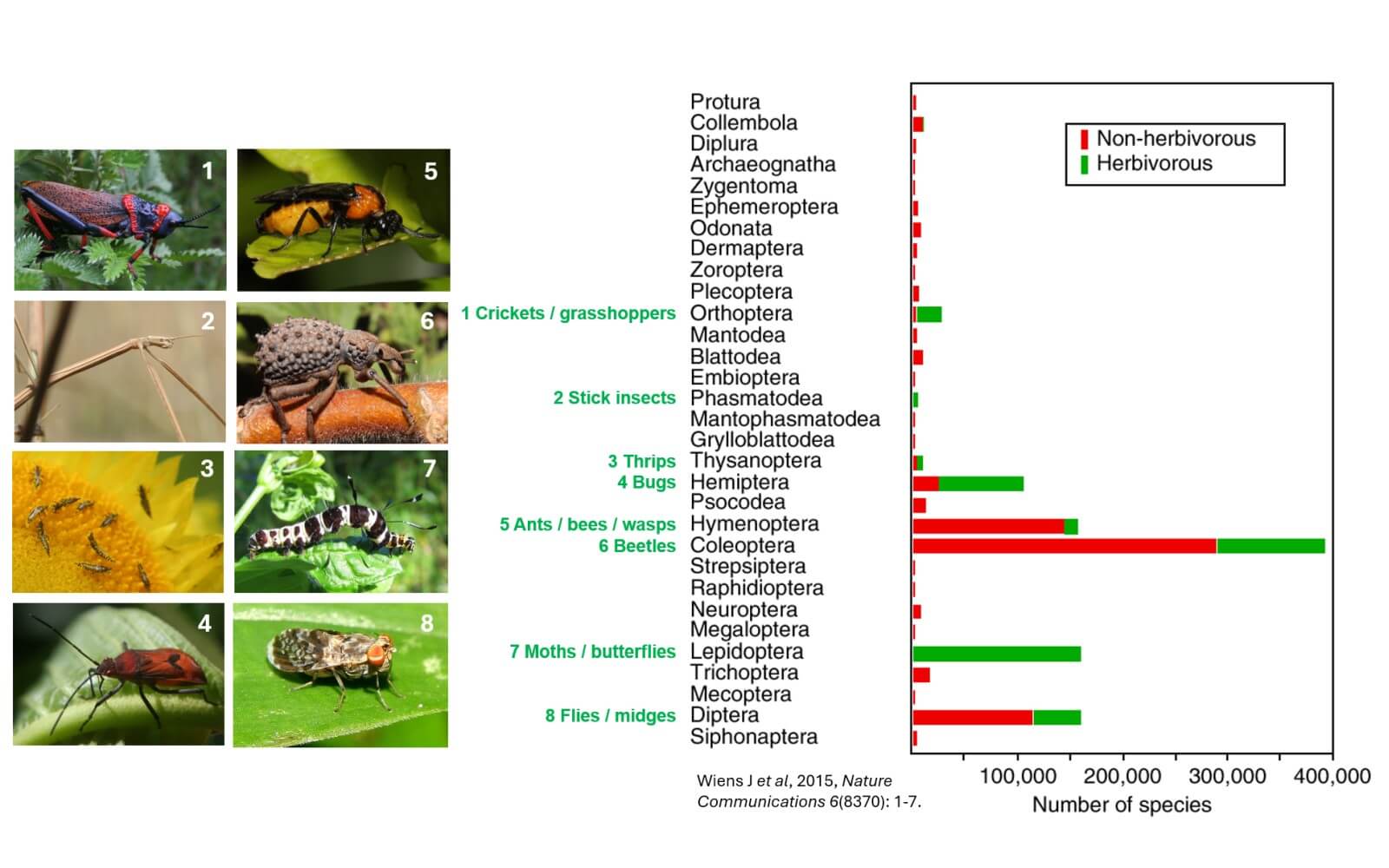

So how many insects eat plants – exactly?

Around 40% of insect species are true herbivores, eating living plant tissues, such as leaves, stems, roots, flowers and seeds (not counting insects feeding on pollen and nectar – which are counted as pollinators).

This chart shows all the insect orders, the number of species in each, and the proportion that are herbivorous (in green).

Insects are fussy eaters

And now we come to the most important part of the story.

What many people do not realise is that plant eating insects are fussy eaters. Insects do not just eat any plants. They eat the food they grew up with, and usually nothing else.

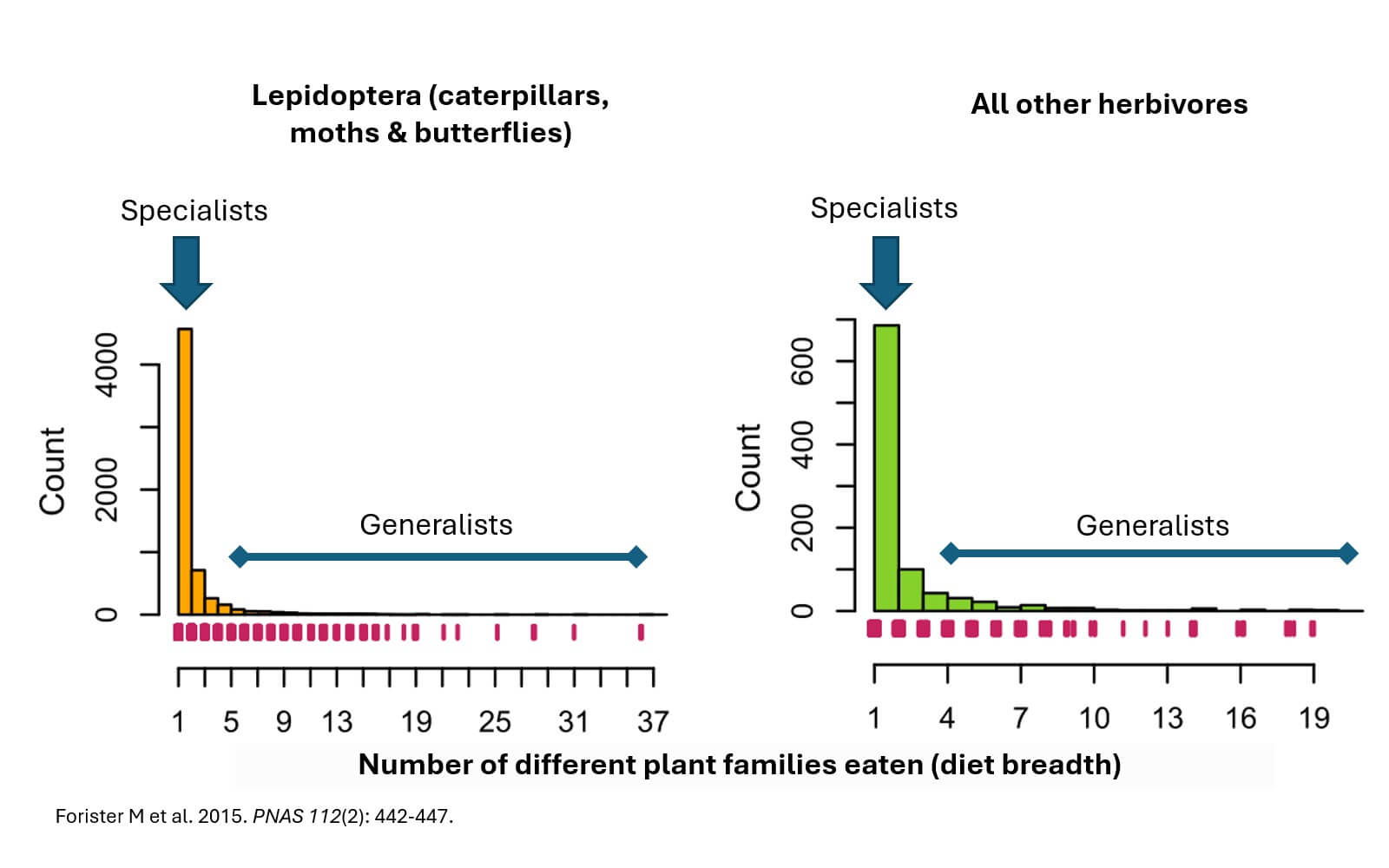

In one study scientists looked at 7500 plant eating insects and 2000 plant species from 165 families. What they discovered was that the vast majority of insects eat only a single family of plants. Many are even completely species specific. The number of generalists, that eat a range of different plants, is very low.

The vast majority of insect herbivores are specialists, that eat only one genus of plants (or even only a single species). Generalists, insects that eat a wide range of plant species or genera, are comparatively rare.

And it’s the same all over the world. Insects are fussy eaters, they eat what they evolved with. There are exceptions, but this is a strong rule.

This explains, why local insects do not tend to eat exotic plants.

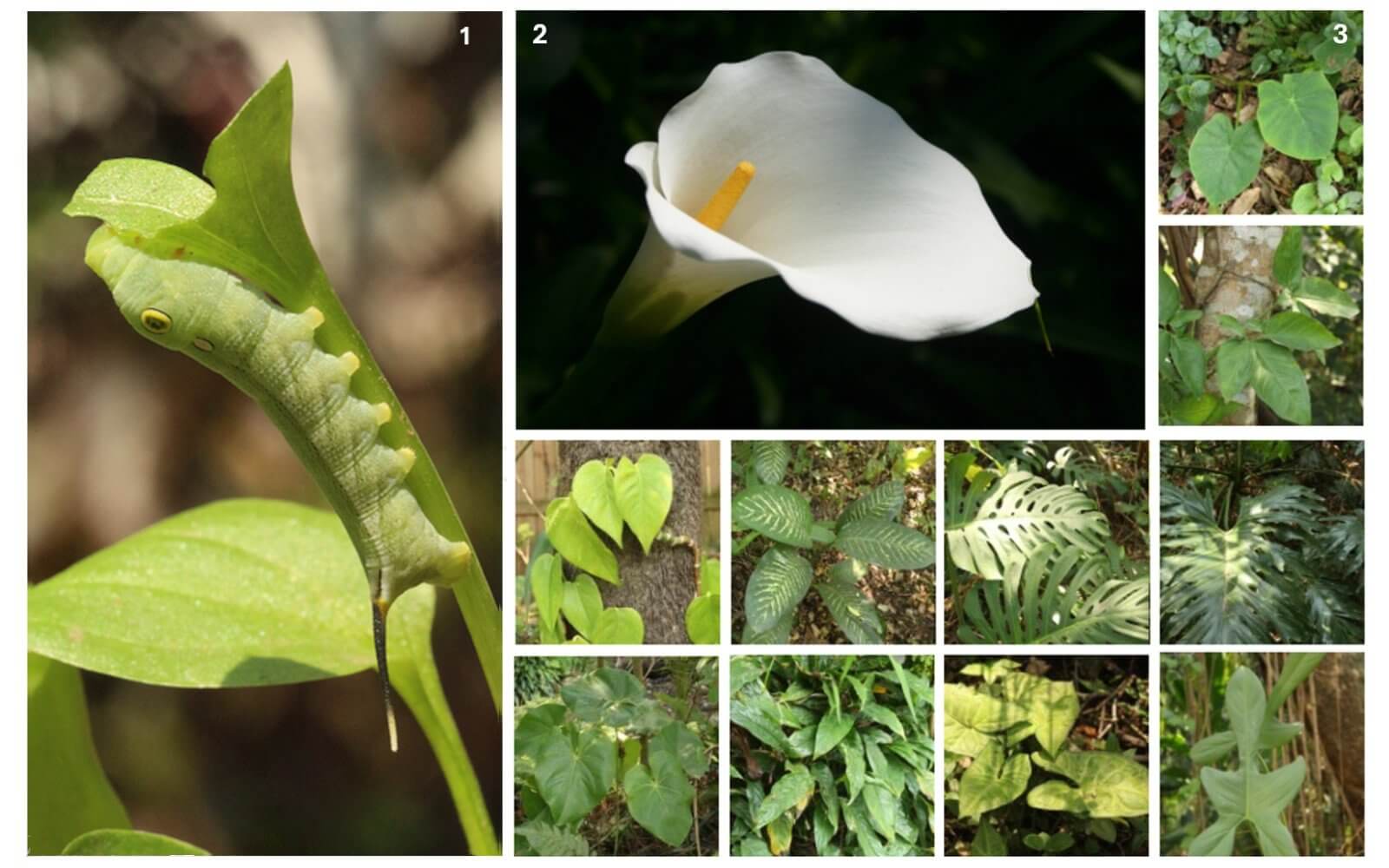

Take this vine hawk moth caterpillar for example (1, Hippotion celerio), which eats our local Arum lilies (2, Zantedeschia aethiopica). When offered a variety of common garden plants belonging to the same family as the Arum lily (Araceae, 3 small pictures), the caterpillar nibbled on one, but refused to eat the rest. It also refused every other garden plant it was offered – about 30 different kinds. Without Arum lily leaves it would have starved.

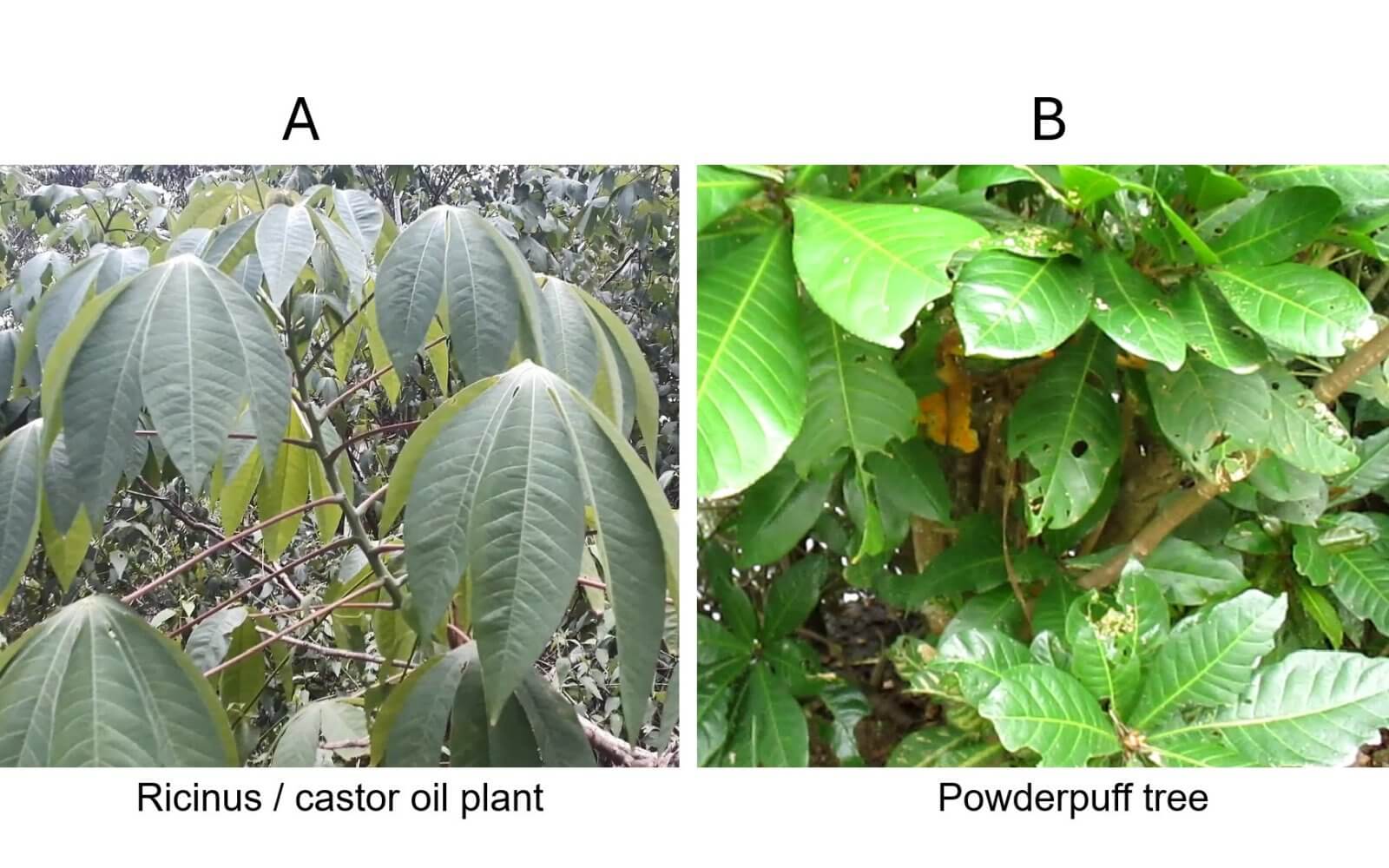

The exotic Ricinus (castor oil plant) has immaculate leaves. This plant is not getting eaten, it is just taking up space. The indigenous powder puff tree on the other hand has been nibbled on. It serves as food for local insects, and therefore its purpose. This is what plants should look like – eaten!

Remember Role 6 – weed control? Plants that don’t get eaten, become ‘invasive’ and create ‘green deserts’, where there is much green but little food.

The plant-insect partnership

Insects and plants form a partnership. Neither can survive without the other. Together they support life on land.

In some cases, plan-insect partnerships are particularly close and exclusive.

The fig tree and fig wasp for example share a long and unique mutualistic association, one that benefits both equally. Figs depend on wasps to make their seeds and distribute their pollen. In turn, the fig tree acts as a womb where the fig wasps can reproduce. This association has existed since the time of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

Fig wasp

Photo: Muchos Insectos

For more than 40 million years there has been a relationship between yucca plants and yucca moths. It’s a particularly important one because neither the yucca or the moth can survive without the other. The moths’ larvae depend on the seeds of the yucca plant for food, and the yucca plant can only be pollinated by the yucca moth.

Orchids release a perfume that mimics the sex pheromones of a fertile female insect, luring in male insects. Overcome by the scent, the males are duped into attempting to mate with the flower. During their futile attempts of copulation, they pick up a gobbet of pollen, so that when they visit another flower they will pollinate it.

Thynnine wasp on a bird orchid

Photo: Michael Whitehead

The world needs indigenous plants

Most insect herbivores depend on specific plant species or families. If these plants disappear, the insects cannot survive.

Most plants need insects to reproduce. If there are not enough insects to pollinate them, the plants will gradually die out.

As plant biodiversity declines, the insects that are left will tend to be the generalists (species willing to eat anything). That is bad news, because these generalists are more likely to attack our crops. For example, the fall army worm.

Specialists that eat only indigenous plants are harmless and beneficial. They are the ones that sustain bird and other animal populations. They are the ones that sustain plant biodiversity and help pollinate our crops.

Nature needs YOU

We need nature but nature also needs us.

We humans have changed more than half of all land area on Earth for our own uses: agriculture, pasture, forestry, cities, industry… Not much of the natural world is left intact.

Does this matter?

Yes, it matters, because nature is built on the food web. If one layer of the food web disappears, the food web collapses, and nature dies.

Let’s look at our gardens, and parks, our school yards and company grounds, our verges, our farm land and every piece of ground.

We need to change our perspective about what is ‘natural’, and what is ‘good’ and ‘healthy’.

If leaves have holes in – that means something is eating this plant, and that means this plant is serving a good purpose in nature, and that our gardens do more than satisfy our visual sensibilities.

Exotic garden plants look so immaculate, because our local insect do not eat them. It’s almost like having a garden full of plastic plants.

When we plant our gardens full of exotic plants, they may look pretty, but they serve no other purpose.

“But the bees and butterflies like them too,” some people argue.

Yes, sure, but bees feed on whatever is available, indigenous flowers – or Coca Cola for that matter. If you truly love butterflies, provide food not just for the adults, but their babies.

“But the birds eat the berries,” say others, about exotic garden plants.

Yes – but birds also eat whatever they can find, and will be very happy to eat the fruit of indigenous plants. Also, remember, most fruit-eating birds need insects in their diet too.

Indigenous flowers look just as pretty, while also supporting life, nature, biodiversity.

“But indigenous flowers just get eaten by pests!” some people complain.

True enough. It is not enough to plant only a few indigenous flowers. Hungry insects will soon find them and eat them. We need more edible biomass for insects in our gardens.

Indigenous trees, which grow up several storeys, provide enough food biomass for lots of harmless, local insects to thrive. Indigenous trees – not exotic trees!

And now, when there is lots of insect food, then the insects come.

The insects in turn attract birds, as well as spiders and insect-eating insects and other vertebrates, who feed on them.

The birds also bring seeds in their droppings. You don’t have to plant everything, some plants arrive on their own.

Now you can even plant those flowers that just got eaten, when they were the only edible food in your garden. But now birds and predatory insects keep the plant-eating insects at bay.

The flowers attract even more insects, then more insect eaters come.

This is a wonderful upward spiral of biodiversity.

This is a healthy ecosystem where many species survive and keep each other in check.

What can I do?

1. Get to know the plants in your garden, and find out what belongs and what doesn’t.

2. Plant indigenous trees, bushes and flowers. The more diverse, the more insects they will attract.

3. Do not use pesticides, herbicides, fungicides.

4. Keep some rotting wood for insect that eat dead wood.

5. Keep a compost heap, use the mulch, avoid bare soil. Don’t dispose of garden waste – it is precious.

6. If you have the space, create a habitat for wildlife by adding a pond.

7. Really, truly help stop climate change.

8. Finally – plant indigenous trees! (or did I mention that already?)

Happy arbour week!

About the author

Marlies Craig is an epidemiologist by training. She has worked for the Medical Research Council, then more recently for the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and is now employed at the WITS Reproductive Health Institute in the Climate Change and Health unit. Though she did originally study Biology and Entomology, her love affair with insects is very personal. In her book What Insect Are You? – Entomology for Everyone, she shares that passion with young and old, see What Insect Are You?. She hopes to kindle in people of all ages enthusiasm and a deeper appreciation of nature and show them why and how they can make a difference. She also started a non-profit organisation called EASTER Action which hopes to promote awareness and action on biodiversity, climate change, and sustainable living, see EASTERaction.org.

About Andrew Carter

Andrew Carter worked as Museum Officer at eThekwini Municipality for 34 years and during this time he put together many of the displays at the Durban Natural Science Museum, including this one on the disappearance of insects.