Has Climate Change really affected our butterflies?

Text and photographs Steve Woodhall Graphics Animal Demography Unit, UCT – LepiMAP

Let’s have an in-depth look at some recent butterfly range extensions

Last issue we began with a spectacular East African butterfly that has definitely become commoner in the Durban area recently. On the face of things this one definitely looks like it has followed warmer conditions southwards.

Forest Queen Charaxes wakefieldi male exhibiting typical Charaxes territorial perching behaviour on the forest edge. Any intruders-not only butterflies, but also birds or dragonflies, are chased away vigorously!

Since 2004, the Animal Demography Unit of the University of Cape Town has been running an atlassing project for butterflies (SABCA-SA Butterfly Conservation Atlas). It began with data gathering from old collections and moved on to targeted field surveys by lepidopterists. By 2010, there were over 120000 records from collections, 25000 records from field surveys, and 12000 records from the infant LepiMAP Virtual Museum, which began in 2006 and has now been expanded to cover all lepidoptera (including moths) across all of Africa.

The sheer volume of data gathered by this Citizen Science project is astonishing. Currently there are nearly 530000 records.

These time-stamped, geo-referenced data records are a powerful resource. They allow the ADU to analyse them and draw conclusions about how distributions have changed over time. This is a useful tool and allows us to dig a little deeper into our suspicions about climate change…

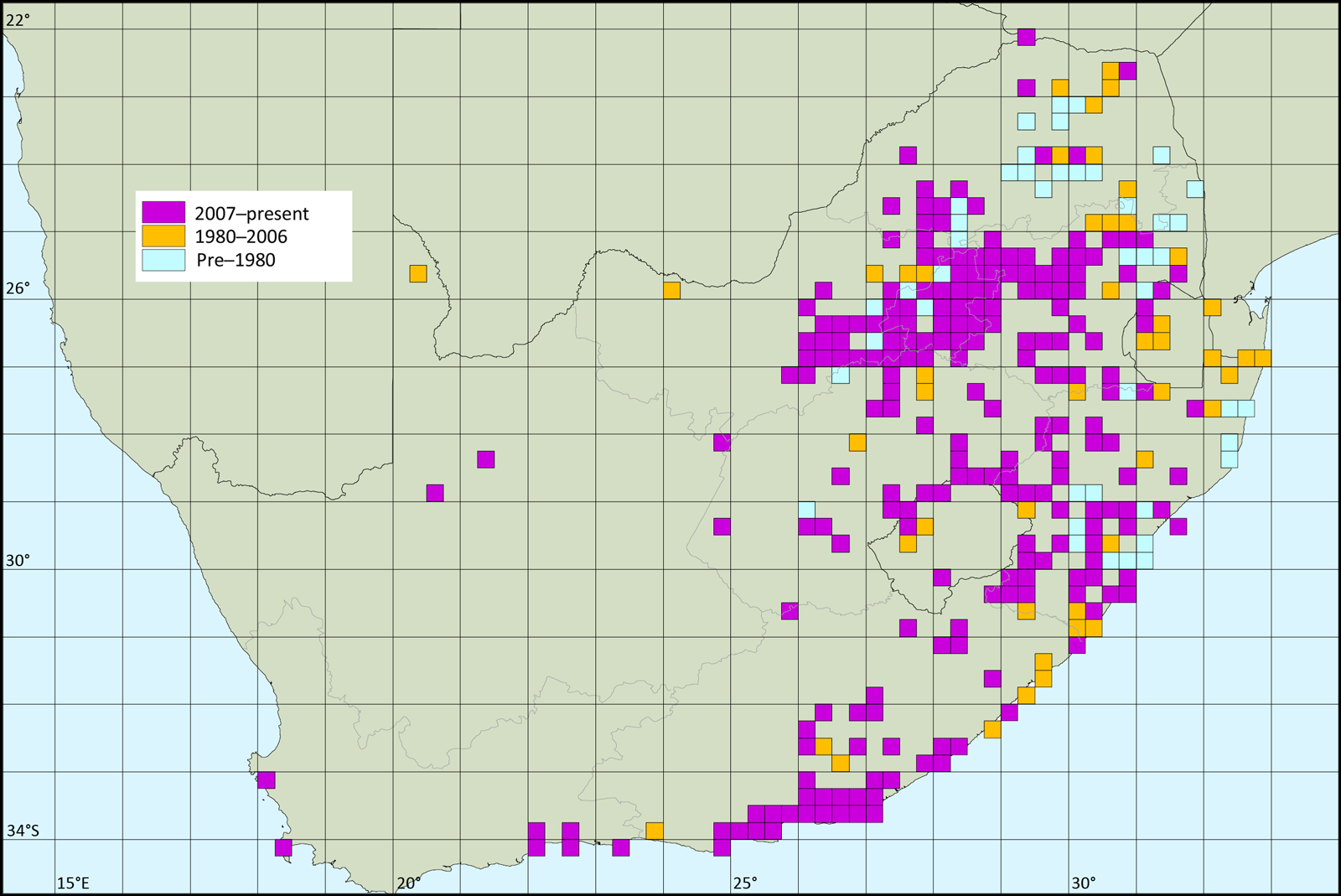

This is the distribution map for the Forest Queen, expressed at the quarter-degree grid square (QDGS) scale. Each square covers a quarter of a degree of latitude and longitude, and shows where a butterfly has been recorded over the past 120 years. The key shows pre-1980 records (essentially pre-climate change and derived from quite scant collection data), records from 1980 to 2006, covering the period when collectors became more active and the targeted field trips started, and from 2007, mainly LepiMAP records.

Although Charaxes wakefieldi was quoted in the previous article as a butterfly whose range has moved southwards, this map shows that the early records are just as widely scattered as recent ones. And it hasn’t been seen in Limpopo in recent years! The most southerly record until 2006 was Scottburgh; now it’s Bazley Beach. So the range may not have changed over time, and what we are seeing here may be the ‘observer effect’. LepiMAP has proved very popular and the graph in fig.1 shows this. However there have been more southerly sightings that haven’t been captured yet… and it took me, the author, 20 years to see one in SA (in Zululand). Nowadays they turn up all over the place, even in the Upper Highway area, and the Bluff. Only continued monitoring will tell us if this really is climate-related.

So what other distribution shifts have happened recently? Let’s look at a familiar, common local butterfly.

White-barred Charaxes, Charaxes brutus natalensis, male perching on a palm leaf. If KwaZulu-Natal had to have a ‘Provincial Butterfly’ it would be this one. He’s a large and robust species, his scientific name is ‘brutus natalensis’, likes his ‘dop’ (he loves to drink fermenting fruit) and to cap it all, he wears a Sharks jersey!

White-barred Charaxes was always a species associated with its host plants-Mahoganies Trichilia sp., and Cape Ash, Ekebergia capensis. And for a long time, its distribution mirrored those of its known host plants. But then along came SABCA…

What was going on here? SABCA’s early records showed White-barred Charaxes turning up in Cape Town, Somerset West, and even Saldanha! And then Gauteng, and points west. Surely this was climate change in action – but a lot of the photo records were of larvae. What were they feeding on? Had the host plants spread so fast?

In the mid 00’s, towns around SA started planting indigenous trees, as a response to pressure from environmentalists. Natal Mahogany, Trichilia emetica, is an attractive shade tree capable of withstanding quite cool temperatures, and I personally saw many newly planted saplings in Somerset West. These must have come from KwaZulu-Natal, and they would probably have been infested with larvae of this common insect.

But that’s not all. For some time, White-barred Charaxes has been known to have switched as a host plant onto the common invasive tree, White Syringa Melia azaderach. I have personally seen females ovipositing on it near Kloof. This tree is common all over South Africa including areas such as Cape Town and Johannesburg. What we are looking at here is probably a mix of host plant shift, anthropomorphic range extension, and (perhaps) the climate in higher latitudes becoming more conducive to its survival.

So, do host plant shifts explain other southwards distribution changes? Here’s one example.

For a long time this attractive butterfly was known mostly from inland grassy areas, where its host plants were members of the family Scrophulariaceae – such as Wild Penstemon, Graderia subintegra. This is a plant of moist, cool grassland. Then, in LepiMAP, it started appearing in places where its known host plant definitely does not occur.

What was driving the range extension into those arid areas to the south and west? And fynbos (a friend of mine photographed one at Silvermine on the Cape Peninsula)? And along the coast?

Craig Peter of Rhodes University, who has worked closely with LepiMAP, was intrigued. He started watching out for the butterflies in the Karoo, and made an interesting discovery.

Females were laying eggs on a roadside weed, Ribwort or English Plantain, Plantago lanceolata. This is a weed of disturbed ground, invasive in South Africa, whose range has spread due to its developed resistance to the glyphosate herbicide Roundup. This butterfly has several other subspecies found around Asia, and some of them use Plantago as a larval host plant. So here we have a range extension driven by a host plant shift… or is climate playing a part as well?

The SABCA/LepiMAP data shows other butterflies whose ranges has shifted southwards recently. One is the brightly coloured Acara Acraea, Acraea acara acara.

This spectacular species carries cyanogenic glycosides in its body tissues. Its gaudy colours advertise that predators won’t find it a tasty meal! Like many Bitter Acraeas its larvae feed on members of the plant family Passifloraceae.

As well as the well-known Granadilla, Passiflora edulis, there are many indigenous African species, such as the genus Adenia – which is well represented locally. In our area, the Mamba Greenstem, Adenia gummifera, is common. This butterfly uses that plant as well as other Adenia species, and as a result is widespread.

Only recently, in 2017, LepiMAP started to show records of this butterfly from the Eastern Cape. Citizen Scientists in Grahamstown noticed it becoming a regular garden butterfly.

The interesting part of this map is the cluster of post-2007 records from the central Eastern Cape. It didn’t take long for Citizen Scientists in this area to start posting records of larvae feeding on garden Granadilla vines…

Although this butterfly is known to use Passiflora edulis elsewhere in its range, it seems to prefer Adenia species in South Africa. LepSoc has another Citizen Science project in its portfolio – the Caterpillar Rearing Group or CRG. This was set up by Hermann Staude in order to gather data on moth life histories for a book he was planning. But it gathered momentum and has struck a chord amongst lady lepidopterists in particular. Hermann recently gave a report back on the CRG’s successes – from knowing only 2% of our local lepidopteran early stages, in a few short years that grew to 13%. And the CRG people have submitted many records of butterfly early stages.

Among these were records of Acara Acraea larvae from Grahamstown. And they were feeding on Passiflora edulis, which is the only member of the Passifloraceae found in that area. So why the recent shift south-westwards? These butterflies are quite strong flyers. Granadillas are grown virtually all over South Africa, so why has it only recently been found outside its traditional range, using this plant as host?

Is it the observer effect again? With more Citizen Scientists attuned to butterflies, what might not have been noticed 20-30 years ago is now being reported? Or is it that before climate change accelerated, conditions in the cooler, southerly areas of South Africa did not allow this butterfly to survive winter? And now, with an acceptable host plant being grown in gardens in these areas, it is free to expand its range as they become warmer?

In the LepiMAP data there are several other examples of butterflies whose ranges have shifted southwards. Some, like the Sabine Albatross White, Appias sabina phoebe, appear to be purely climate-driven. Others, like the Yellow Pansy Junonia hierta cebrene and Palm-tree Nightfighter, Zophopetes dysmephila, appear to be directly connected to man’s interference with their host plants’ distribution patterns. It’s easy, with today’s focus on anthropogenic climate change, to blame it for all changes we see in nature. It certainly appears that mankind’s appropriation of natural resources to his needs for fuel and food are destroying more and more critical habitat. The deforestation in tropical rainforests, and the effects of ocean pollution and over-harvesting of fish stocks, are plain to see.

But the effects of climate change are more subtle. Often, they appear to exacerbate the harm done by other man-driven changes, but their direct influence can be hard to prove. This results in ‘deniers’ finding ready support for their stance. Considering the bigger picture, climate change appears to be a major factor behind all the worrying problems the world is facing. But to some (not this author, I hasten to say) the Jury is still out. Conservationists need to be constantly watching for the footprints of climate change. Projects like LepiMAP and the Caterpillar Rearing Group allow members of the public to help detect them.

Steve Woodhall is a butterfly enthusiast and photographer who began watching and collecting butterflies at an early age. He was President of the Lepidopterists’ Society of Africa for eight years, and has contributed to and authored several books, including Field Guide to Butterfl ies of South Africa and the popular What’s that Butter fly? His app, Woodhall’s Butterflies of South Africa, is described as the definitive butterfly ID guide for South Africa.