The power of the pen

An interview with Tony Carnie

Text Paolo and Rob Candotti Photographs Tony Carnie

“When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

Sherlock Holmes

At the heart of great investigative journalism lie two important traits: a passion for detection and a love of truth.

Both detection and truth tend to act as searchlights that expose human error or human tyranny – elements that prefer to remain under cover of darkness, even by individuals who often conduct their business in the public domain.

These individuals are usually obsessed with some form of social engineering, but are insensitive to their own accountability. Oblivious, or in denial of the damage they leave in their wake, they protect their reputations and agendas with tenacious ferocity and often employ a sophisticated machinery of public relations to keep detection at bay.

The hope, and the vanity, of every reporter is that they will find a crack in their armour, or a fingerprint in the fractures they leave behind from which they can prise their most valuable material – information. In this sense every investigative journalist must possess the skills of an accomplished detective and what Arthur Conan Doyle would call “the nose of a seasoned bloodhound.”

In that regard Tony Carnie sits with illustrious company of legendary international investigative journalists which include South Africa’s own Max du Preez, who is widely respected, amongst other things, for exposing apartheid’s Eugene de Kock for crimes against humanity.

“I don’t know where I’m going, but I’m on my way.”

Carl Sagan; Astronomer, Cosmologist & Author

Tony wasn’t born with a mission – he acquired one.

Whilst a love for the environment is often sparked at an early age, this was not the case with Tony who had to wait for nearly 20 years before his passion blossomed into shaping the influential articles he writes today.

Born in what was an environmental paradise in Kenya and then raised in biodiversity-rich Zimbabwe, Tony did not perceive the steady deterioration of our eco-systems as an important issue in his early years.

He does, however, recall the annual family trips from Nairobi to Mombasa, and on occasions having to stop for half-an-hour to wait for a seemingly endless herd of majestic elephants lumbering grandly across the road in Tsavo National Park.

Tony accepted those memory-etching occasions as the norm, but the possibility that in the future they would be a thing of the past, never crossed in his young mind.

“When I think back, I suddenly realize that it’s something neither you nor I are likely to experience again,” he said sadly.

After completing his schooling at Marlborough High School in Harare, Tony found himself at a loose end and without any clear career aspirations.

He had considered becoming a vet, or even studying archaeology, but with his mother’s guidance he eventually decided to exploit his good English writing skills and enrolled in the Zimbabwe Institute of Mass Communication to train as journalist.

Soon he was working long hours as a court reporter at The Herald.

The hard lessons of being in the public domain came quick and fast and Tony recalled one of his more clumsy faux pas during his early years as a court reporter. He described the circumstances around an article he wrote for The Herald while covering the trial of two former spies who had been charged with illegal possession of arms and ammunition.

“Members of the court had difficulty containing their amusement when a member of the Central Intelligence Organisation came to the witness stand to give evidence, wearing what appeared to be a false moustache and glued-on sideburns. Their dark, bushy appearance was noticeably different to the witness’s straight, blondish hair.”

Caught up by the drama and clandestine nature of the trial, Tony had allowed his imagination to run ahead of the facts and had assumed (incorrectly) that the witness had adopted an amateurish disguise, whereas the false moustache and glued-on sideburns were far from false, and even further from glued.

He had to publish his first correction after a very irate intelligence agency official phoned his editor the following morning to vouch for the fact that the spy’s sideburns and moustache were in fact, quite authentic!

Tony recalls with some amusement, another event when he was invited to attend the launch of a clean-up campaign in Durban in the early 1990s.

“I was usually allocated a photographer for such occasions but none was on duty, so I grabbed an office camera and dashed to the event where Mayor Margaret Winter was hosting the function and offered a photo-shoot for the journalists present.

Not knowing much about photography, but determined to be “creatively different” I decided to try something unusual and after much discussion persuaded the well-dressed mayor to get into a “wheelie-bin” for a few exclusive photos!

It took a while to find a spotlessly clean bin and even longer to get the mayor inside it, after which I clicked happily away while the mayor got into the mood of the occasion and posed with appropriate gusto!

Feeling rather smug with my creative photography I rushed back to the office to meet the print deadlines, only to find that I had forgotten to insert a film in the camera!

For some time after that, I studiously avoided any function where the mayor had been invited!”

On another somewhat more challenging incident he applied his investigative skills to gate-crashing an exclusive function and sneaking an interview with Margaux Hemingway, the actress and fashion celebrity.

Hemingway had been invited to St Lucia (now iSimangaliso Wetland Park) to promote the eco-tourism potential of the area, but a competitor’s newspaper had secured exclusive interview rights.

Not to be outdone Tony, together with a journalist friend, scoured the game reserves of the area to find out where the star might be staying. Their investigative instincts bore fruit and they soon identified the hideaway being used to host Hemingway. That, however, proved to be the easiest part of the challenge.

Having established where the star was being hosted, they still had to get past all the security systems to have any chance of a face-to-face meeting.

Fortunately, a co-operative ranger tipped them off as to where the key to an unguarded ranger’s gate was hidden and armed with pen, notepad and a fair dose of audacity, they soon presented themselves in front of Dr Ian Player, who was hosting the actress.

In a surprise move, Dr Player commended them for their entrepreneurial skills and magnanimously allowed them to interview the statuesque Hemingway, much to Tony’s delight and that of the editors back in Durban.

“it’s funny how day by day, nothing changes. But when you look back, everything is different.”

CS Lewis, Novelist

Tony’s first taste of how governments can mute the voice of journalism began in the 80s when Robert Mugabe’s regime first began to realise that the local and international press where now criticising them for adopting the same repressive violence and intolerance so beloved by their predecessors, and systematically began threaten or shut down the free press.

He quickly moved to Durban where he considered applying for a post with the then Natal Parks Board. It was there where his first tentative interest in conservation emerged.

However, a call from The Natal Mercury put paid to that and he was soon on the beat as a general reporter. His first meaningful interaction with environmental issues occurred when he was asked to report on the potential mining of St Lucia in the late 80s.

Tony was impressed with the effectiveness of the environmental lobby at the time, which was well organised and influential. He recalls the powerful role played by the Wildlife and Environment Society of South Africa (WESSA), and to some extent this influenced his decision to focus on issues of conservation.

Suddenly Tony had to study and analyse matters which he was ill equipped to do.

So, for inspiration and guidance, he looked to the writing of other environmental journalists and recalls admiring the work of James Clarke at The Star and the then doyen of environmental journalists, John Yeld at The Cape Argus.

Keith Cooper of WESSA, although not his journalistic mentor, provided frequent encouragement and always made himself available to explain, or to comment, on a wide range of issues, including the destruction of the Dukuduku Forest near Mtubatuba and the many threats to the Wild Coast, from the building of illegal cottages to the detrimental impact of toll roads and mining.

But it was the work of the American environmentalist Peter Montague that galvanized Tony’s focus.

Peter is the co-founder and director of the Environmental Research Foundation in Annapolis, which focuses on providing community organizations with information about environmental problems that are relevant to their lives. His articles and their impact were so impressive that Tony made a point of contacting Montague when the opportunity arose for him to visit America.

For many years Montague has published the highly influential environmental justice e-newsletter, Rachel’s News which adopts a philosophy that Tony now shares. This is the belief that ordinary citizens, once supplied with quality information, can be more powerful agents for change than any organisation or government.

“Never theorize before you have data.

Invariably you end up twisting facts to suit theories,

instead of theories to suit facts.”

Sherlock Holmes

This philosophy can be easily seen from Tony’s writing style, in which he firstly provides thoroughly well researched information and secondly goes to great lengths to ensure that all sides of a story are balanced and fair. It is only through this type of unbiased evidence that readers are encouraged to reach their own conclusions on issues that are vital to them.

Armed with this template, Tony soon started building a reputation as a fearless reporter and his regular insightful columns in The Mercury were rewarded with several awards.

The most significant of these was the CNN African Journalist of the Year (Health/Medical Category) which he received for a series of articles he wrote in September 2000. In these articles he exposed the links between air pollution and cancer in young children living near the petrochemical complexes in the South Durban Area at the beginning of the new millennium.

He remembers the investigation as being intensely difficult and complex, taking many months of exhaustive and time consuming work.

A quote Tony used from a CSIR study written three years prior to his investigation sums up some of the frustrations and complexities:

“There is no doubt that some of the chemicals and pollutants wafting around south Durban can kill you. Most of the current information is based on guesswork, estimates and speculation rather than physical measurements of the air which people take into their lungs.”

If data on the quality of breathable air was riddled with speculative mist, then even denser fog was added by conflicting statements from respected authorities such as the Cancer Association, which insisted that residents subjected to the industrial pollution were more likely to die from cancer contracted through smoking, bad diet and emissions from road vehicles!

But the public complaints and new cases being reported were just too many to ignore, so Tony embarked on a long, investigative mission to collects the facts. This often necessitated going door to door in the middle to low income suburbs of Wentworth, Merebank and the Bluff, developing the trust of families and patiently collecting the anecdotes and data that he needed to establish the truth.

Analysing information is often about detecting patterns, statistics and behaviours that vary from the norm. The more Tony dug, the deeper the hole became.

“The rate of leukaemia (blood cancer) in young children in Merebank, Durban, appears to be 24 times higher than in other parts of the country, and the rate of all other cancer cases was four times higher than the national rate.

These calculations were done by public health specialist Dr Duane Blaauw from the UKZN’s Nelson Mandela Medical School, based on cancer cases found in my door to door and phone survey.

Blaauw compared the incidence of leukaemia and cancer in Merebank children (under the age of 10) against national statistics for this age group over the past 10 years. He concluded that although calculations were based on a very small sample of children, the results were unlikely to be a fluke or chance result.”

As his work began to uncover the full horrors of creeping pollution, it was not its deadly spread that shocked him the most, but the irreversible effects it had on the most innocent of all victims – the children living in the area.

In his interviews with them what Tony vividly remembers most was their haunted eyes, their fragile bodies and their slow, lingering journey towards death.

“18 Tambotie Street – Thirteen-year-old Sherry Smit was diagnosed with SLE (systemic lupus erythematosus – an uncommon deadly disease) at the age of eight and is now in partial remission after intensive chemotherapy. She will probably be on cortisone treatment for the rest of her life.

The plucky little teenager smiled bravely when I visited her and she told me of her great love for animals. But she is in obvious pain. She walks slowly, like an old woman, because of crippling pain in her swollen heels and knees, and her body has been bloated from the cortisone.

134 Dunville Road – Bronwyn Campbell, 15, died in September 1997 after being diagnosed with SLE earlier the same year. The former Grosvenor Girls’ High School pupil had lost 15kg and was unable to walk just before she died.

In the house next door (133 Dunville Road), three-year-old Geraldine MacDonald died of kidney cancer in September 1994.”

The battle against air pollution in the Durban South area was a collaborative effort, driven by a number of prominent community leaders and organisations and Tony feels proud that his contribution of hard evidence finally exposed the shocking truth to the nation, through the voice of The Mercury.

The combined pressures eventually forced the government, under the then Minister for Environmental Affairs, Valli Moosa, to install programmes to rectify the situation.

Interestingly, the most recent analysis on the state of biodiversity in eThekwini indicates that air quality is the only environmental measure where the city has improved in the past 10 years!

Whilst the CNN Award gave Tony international recognition for his consummate in-depth reporting, he considers a certificate he received from the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance among the most meaningful of honours he has ever acquired.

The unpretentious certificate was handed to him by the community, without any pomp or ceremony, and it reflects a simple tribute:

KEEPING THE PRINCIPLES OF ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE ALIVE

No matter how balanced or objective Tony’s reporting may be, exposing human error that creates human suffering, inevitably exposes human frailty and incompetence.

This exposure does not often bring out the noble in most human beings. And when big business, or big egos are involved the situation often morphs into complex denials and lack of accountability that never serves the public interest.

Subtle pressures can, and often are placed on editors to tone down, or give less prominence to controversial issues, especially ones that involve conspicuous public figures.

There is an old saying that the first casualty of war is the truth.

But Tony’s fear is that the first casualty of South African politics may be journalism. Not only because its voice is constantly under threat from individuals or pressure groups, but because it is in danger of becoming the slave of the powerful, instead of the servant of the people.

“All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed, second, it is violently opposed, and third, it is accepted as self-evident.”

Arthur Schopenhauer, Philosopher

Tony has been fortunate that he has never flinched from reporting the facts he has collected and he has not had to bow to external pressure.

However, he has expressed some concerns that there may be subtle changes taking place in the South African media at present and that the influence of big business and politics may soon take their toll on the free press.

This can be clearly seen in the next major environmental battle that is looming on the horizon, driven by extensive pressure from mining and oil companies who, in conjunction with vested political interests, are taking advantage of the chaotic state of mining legislation.

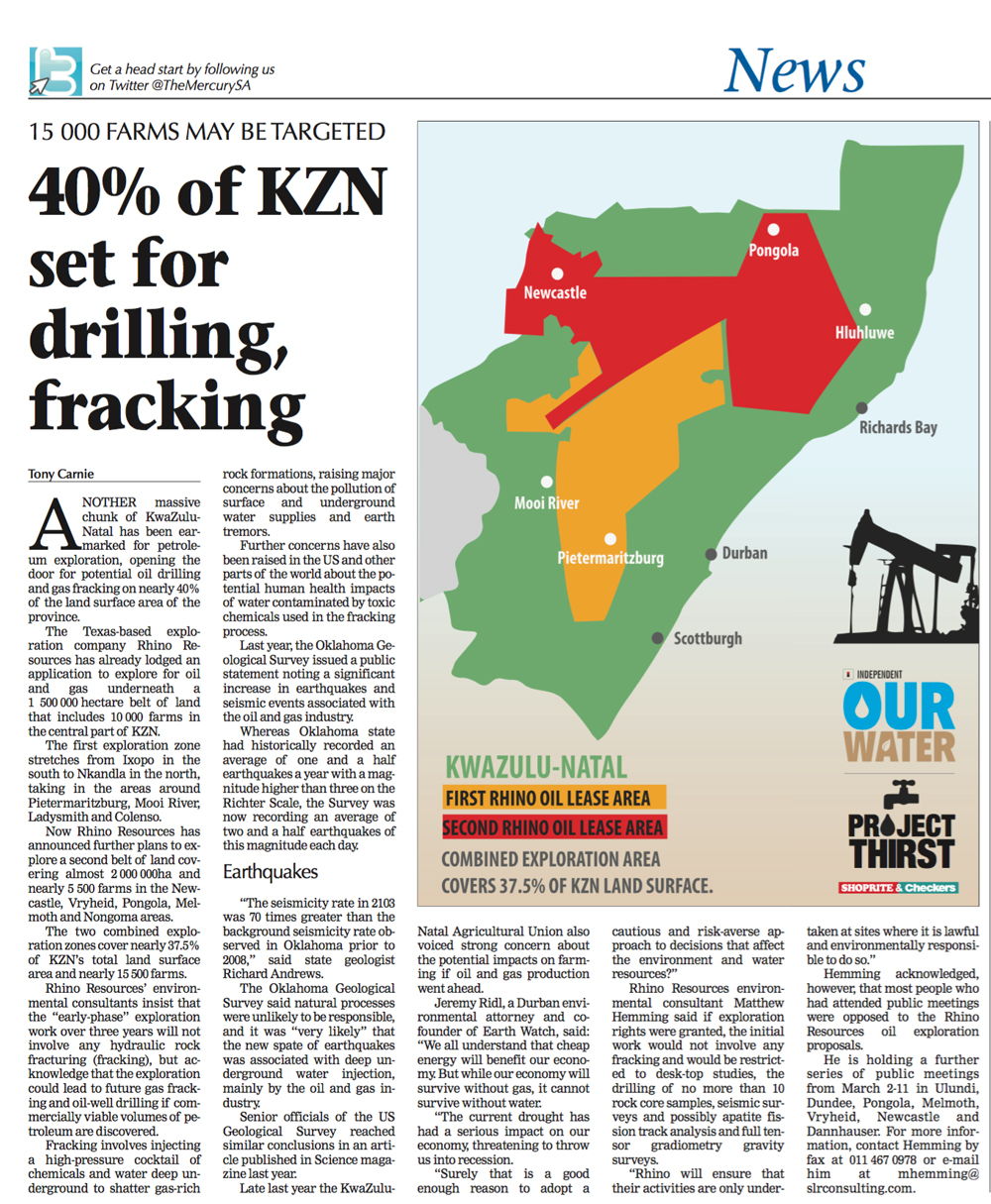

Namely, the fracking controversy.

The social and ecological consequences of gas extraction are complex and how governments respond to this new technology will be crucial.

On a national level, it is argued that shale gas is a step towards energy independence. But in the rush to drill, concerns about the potential hazards of fracking are already being swept aside.

One of the key problems with fracking process is that toxic chemicals can seep into the local drinking water and the cumulative impact of dumping potential lethal waste without adequate oversight, is a catastrophe waiting to happen.

But the lure of a new domestic energy source and the promise of jobs in regions starved of investment may prove a temptation too hard to resist.

Pressed for comment Tony explained:

“I have deep concerns on an issue that is likely to have short term gains for a selected few, but long term negative consequences for those who are left on the land, once the shale gas is exhausted.”

Government’s tacit support for fracking ostensibly as an avenue to economic salvation does not bode well for the environmental lobby. Tony has written a number of articles on the subject already, and has aired numerous points of view.

The battle is, however, only just beginning.

“Information is the lifeblood of a free, democratic society.”

Robert Kaiser, former reporter and managing editor of The Washington Post

Environmental issues remain at the centre of Tony’s crosshairs and for him the question of the future remains paramount.

“My concern is that the environmental lobby appears to have weakened in recent years from the heights of the WESSA era and that officials and editors today don’t take environmental issues as seriously as they should.”

Having said that, he reiterated his commitment to empowering readers with well researched and detailed information in the firm belief that in doing so his reports would help to make a difference.

A statement by the late environmental icon Dr Ian Player made at the 2006 SAB Environmental Journalists awards sums up the significant contribution Tony Carnie has made, and is making, to environmental issues in KZN.

“Tony covers green and brown issues without fear or favour and has earned the respect of friend and foe alike. He has become one of the most influential and intelligent journalists in the environmental field today.”

But the task is never easy.

Most investigative journalism is a thankless endeavour, time and energy-consuming, that will often generate impatience in editors and intolerance in powerful people.

The results of Tony’s work are not often glamorous. Investigations can be lengthy, exhausting, dispiriting and mundane.

But whether it is drilling down into the dark heart of an individual, or the factors that may constitute a national or global disaster, the victims are almost always living creatures, and these constitute a narrative that often reveals characters and stories that are as complex and tragic as the most powerful fiction.

There is a nobility and courage in writing these stories.

Because these are the stories that the world deserves to know.

Two uncommon values from a true member of the Eco-Impi.

“You can’t be a wimp and be a good investigative journalist.”

Max du Preez, Author & Columnist

More of Tony’s adventures

“In March 2011 I was invited to attend the opening ceremony of the new research base station at Transvaal Cove, Marion Island. Since the island was annexed in 1947, an assortment of ramshackle prefab buildings were built to house a series of research teams. But it is a very harsh environment (cold, wet and windy – with rain for 317 days of each year) and by 2000 most of the buildings were falling apart and leaking.

So work on a brand new, much modernised base station began in 2003 with new labs and sleeping quarters etc. It took almost decade to finish and I went with a party of journos to cover the opening. Seen from the air, the base station resembles the Y-shaped SA flag.

But there was much more to the trip than that. The Department of Environment Affairs arranged for several senior researchers to accompany us, and they gave us several very enlightening briefings during the five-day voyage from Cape Town to Marion (history, scope of research activities on sea birds, climate change etc.) and we also got to walk around part of the island to visit the penguin and seal colonies – with one rare and gloriously sunny day and one horribly went and windy day.

I think if was one of the highlights of my career, getting to visit such a unique and remote island that has a truly astonishing wealth of seabirds and animal life and which remains largely undisturbed by human influences.”

“These photos are from the regular Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife game capture programme in which rhino and other valuable species are caught and sold annually at the KZN game auction. I have covered a number of game captures and had a few close shaves. Back in the days before digital cameras I was waiting on the airstrip inside Imfolozi game reserve while a chopper darted a pair of rhinos from the air. The drugged animals are then driven by the chopper towards flattish, open terrain so that they can collapse in relative safety once the immobilising drugs take effect. As this was unfolding, my camera ran out of film and I was concentrating so hard on swiftly inserting a fresh 36 frame film cartridge into the camera that I failed to notice a one and half ton white rhino emerge from the bush at speed just a few meters away. Fortunately, a colleague screamed a warning to me and I managed to scramble behind a truck to get out of the way of the horns.”

“This was a massive fire at a 14 million litre petrol storage tank at Engen’s refinery in Tara Road, Wentworth in 2007. It burned for several days and was visible from several parts of Durban. The heat was intense, even from more than a hundred meters, from where I took this photo. The refinery has been a source of great controversy for decades because of harmful petroleum and benzene emissions very close to the densely-populated residential areas of the Bluff, Wentworth and Merebank.”