Minnows to Monsters: some residents of Krantzkloof rivers

Text Tim and Nick McClurg Photographs Tim McClurg

While much of the terrestrial flora and fauna of Krantzkloof has been well described, we perceived a gap in the aquatic domain where no concerted effort has been made to evaluate the fishes and larger invertebrates inhabiting the rivers and streams. This article summarises our attempt to fill that gap. The survey was conceived and performed in our private capacities. We hope that it will increase awareness, spark further interest and contribute information for conservation planning. Electronic copies of the full report may be obtained from or the authors (mcclurgs@telkomsa.net).

The study area

Our survey covered the lower catchments of Molweni and Nkutu rivers, which together drain a large portion of the “upper highway” area west of Durban. The study area stretches from just below the Acutts Road Bridge to a position shortly before the confluence of the combined Molweni/Nkutu and Umgeni Rivers. Nine sites, which we considered to be reasonably representative of the study area, were selected. Given that the sampling intensity was very low and widespread, the report should be regarded as an initial assessment rather than a comprehensive survey.

The study area

Sampling sites

While the habitat along the much of the upper reaches of both rivers can be loosely described as “mixed urban”, this changes to relatively pristine scarp forest once the rivers enter Krantzkloof Reserve. Lower down, towards the Umgeni confluence (Sites 8 and 9) it reverts largely to rural grassland.

Typical habitat along the Upper Molweni River within Krantzkloof.

Methods

We used backpack electrofishing to sample the river fauna. This method is less harsh on the environment than traditional methods (cast nets, seine nets, gill nets and traps). In essence it uses an electric current to temporarily immobilise fish and crustaceans. These may then be gathered in a net and taken ashore for processing (identification, counting, photography etc.). Recovery is rapid and the animals are released.

Electrofishing

Species descriptions

Eleven species of fish and six crustacean species were recorded. Brief descriptions of each are given here, together with their current conservation status as determined by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This organization evaluates and monitors the status of all global species which may be facing extinction (red data species). They are rated in one of nine categories: “not evaluated”, “data deficient”, “least concern“, “near threatened”, “vulnerable”, “endangered”, “critically endangered”, “extinct in the wild” or “extinct”. We have added an “alien invasive” category to our study to distinguish organisms that are non-native to the ecosystem and may impart negative impact by, for example, disrupting ecosystem functioning or impairing biodiversity.

1. Longfin Eel Anguilla mossambica

Least Concern.

This charismatic fish was recorded both above and below the escarpment. It is common along much of the east coast of Africa and occurs in Madagascar and some Indian Ocean islands. It has a remarkable life history (termed catadromous), which includes distinct marine and freshwater phases.

Nick McClurg with an adult Longfin Eel.

Marine larval “glass eels” enter river systems (via estuaries) where they change into “elvers”. These migrate upstream, deftly circumventing man-made and natural barriers. After attaining a length of about 30 cm they tend to settle in a particular stretch of water to fully mature. They may remain there for decades before they return to the sea to spawn the next generation of glass eels. Their nocturnal and secretive habits afford some protection from predation. However, in built-up areas they face the additional threat of harassment by mankind and dogs. There are a number of large resident eels in Krantzkloof and it is important that they are afforded respect and protection.

2. Freshwater Goby Awaous aeneofuscus

This species has not yet been evaluated by the IUCN.

We recorded them in the lower catchment near the Umgeni confluence. While most gobies inhabit inshore marine waters, a number of species worldwide are found in estuaries, coastal lakes and rivers. Awaous aeneofuscus is prominent along the east coast of South Africa. It is found in running water and pools. They dwell on the substrate and prefer sand as this allows them to hide by burrowing. In common with most gobies its pelvic fins are united to form a disc to aid manoeuvring on the substrate. Its upward-directed eyes provide evidence of its benthic lifestyle.

Freshwater Goby

3. Sharptooth Catfish Clarias gariepinus

Least Concern.

They are widely spread across Africa. This reflects their hardiness, which is based on an ability to breath air, survive desiccation of the environment and move overland. Live specimens were recorded above the Nkutu waterfall and the upper skull of a larger specimen was recovered below the waterfall. It may attain 59 kg and is widely valued in subsistence fisheries, aquaculture and angling.

Young Sharptooth Catfish

Skull of a large Sharptooth Catfish

4. Redtailed Barb Enteromius gurneyi

Redtailed Barb (Enteromius gurneyi) was recently re-graded by the IUCN from “vulnerable” to “threatened” due to rampant habitat loss.

It is endemic to a restricted area in Kwazulu Natal and is mostly found in clear waters flowing through the sandstone belt at altitudes between 300 and 1000 metres. We recorded it in the Molweni River above Kloof Falls. Its presence in Krantzkloof is highly significant and it is imperative that it is afforded ongoing protection.

Breeding male Redtailed Barb

5. Bowstripe Barb Enteromius viviparous

Least Concern.

This close relative of the Redfin Barb has a considerably larger home range extending further inland and covering the coastal plains between southern Kwazulu Natal and northern Mozambique. We recorded it in the Molweni River above Kloof Falls.

Bowstripe Barb

6. Kwazulu Natal Yellowfish Labeobarbus natalensis

Least Concern.

Southern Africa is home to a number of Yellowfishes, some of which attain a fair size and are targeted by anglers. Most species have restricted home ranges and may be vulnerable to extinction. The Kwazulu Natal Yellowfish, known colloquially as the “scaly”, is found between the Mkuze and Umtamvuna Rivers. We observed it near the Molweni/Umgeni confluence.

Kwazulu Natal Yellowfish

7. Largemouth Bass Micropterus salmoides

In its home range (North America) it is rated by the IUCN as being of “least concern”.

In South Africa it is clearly an “alien invasive”. This voracious apex predator may attain 10 kg and is a popular angling species. It was introduced to South Africa in 1928. When they invade natural waters they pose a serious threat of damaging, or even eliminating, indigenous species. We have found it in the Upper Molweni River and near the Umgeni confluence. Largemouth Bass pose a significant threat to ecological integrity of Krantzkloof Rivers and streams.

Young Largemouth Bass

8. Mozambique Tilapia Oreochromis mossambicus

Vulnerable.

This hardy member of the cichlid family is common and widespread in rivers along the east African coast and is widely dispersed in inland regions. It tolerates brackish or marine conditions and thrives particularly well in standing waters. It is a valued target for anglers and holds great potential for aquaculture and subsistence fisheries. We recorded it in the upper and lower Nkutu River and near the Umgeni confluence. The IUCN rating of “vulnerable” is due to the fact that, over much of its range, it is actively hybridizing with Oreochromis niloticus and may disappear as a distinct species.

Young Mozambique Tilapia

9. Southern Mouthbrooder Pseudocrenilabris philander

This species has not yet been evaluated by the IUCN.

Also a member of the cichlid family, it occurs in a wide variety of habitats from southern Kwazulu-Natal to Lake Malawi and tributaries of the Congo River. Its common name is derived from their typical cichlid breeding behaviour, which involves nest building and extended brooding of the eggs, larvae and juveniles. Their bright colouration and interesting behaviour have gained them favour as a target for aquarists.

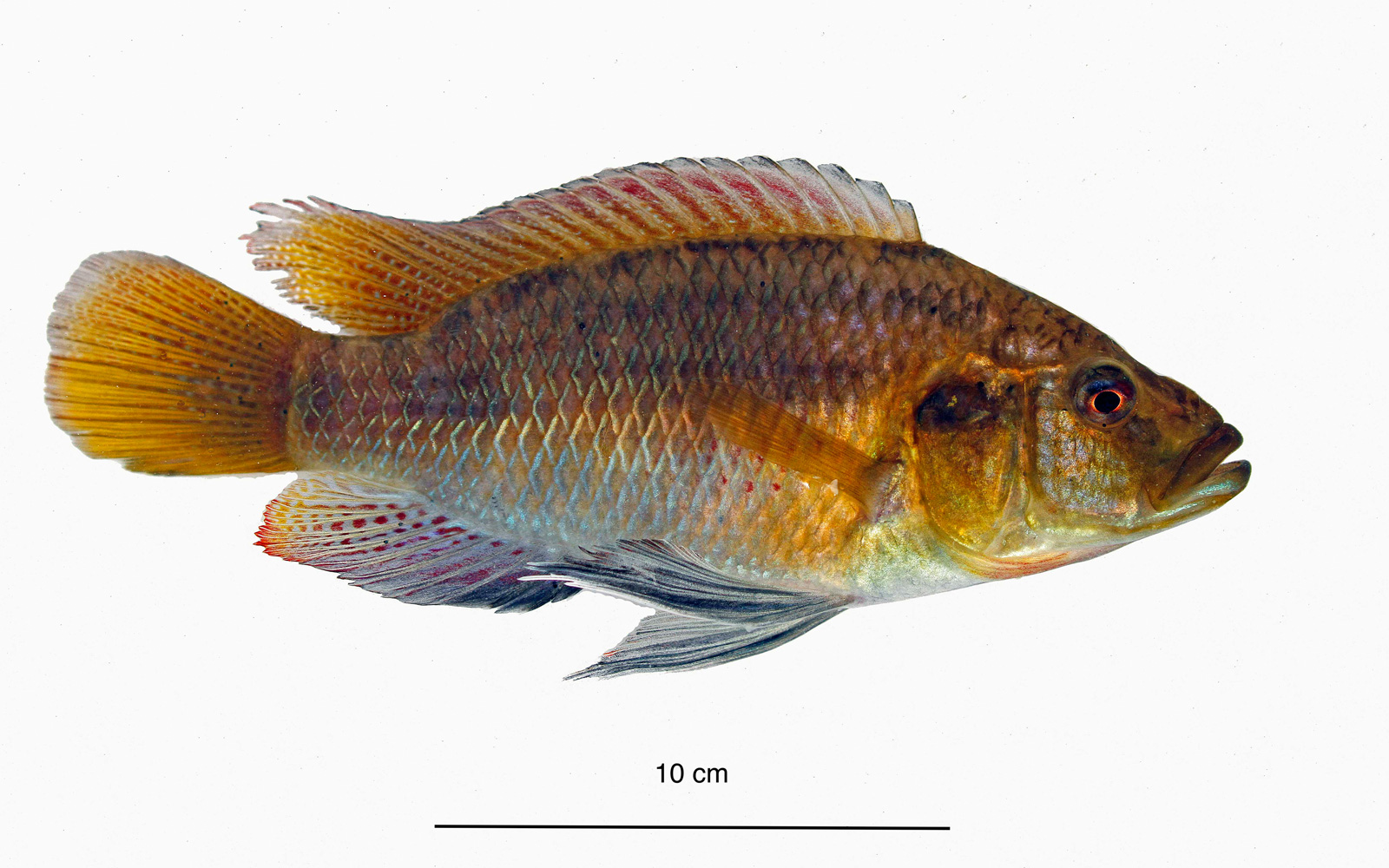

Breeding Male Southern Mouthbrooder

10. Banded Tilapia Tilapia sparrmanii

Least Concern.

This, the third member of the cichlid family to be encountered in our survey, has much in common with its relatives in terms of morphology, distribution and behaviour. However, they tend to be less colourful and are consequently targeted less often by anglers and aquarists.

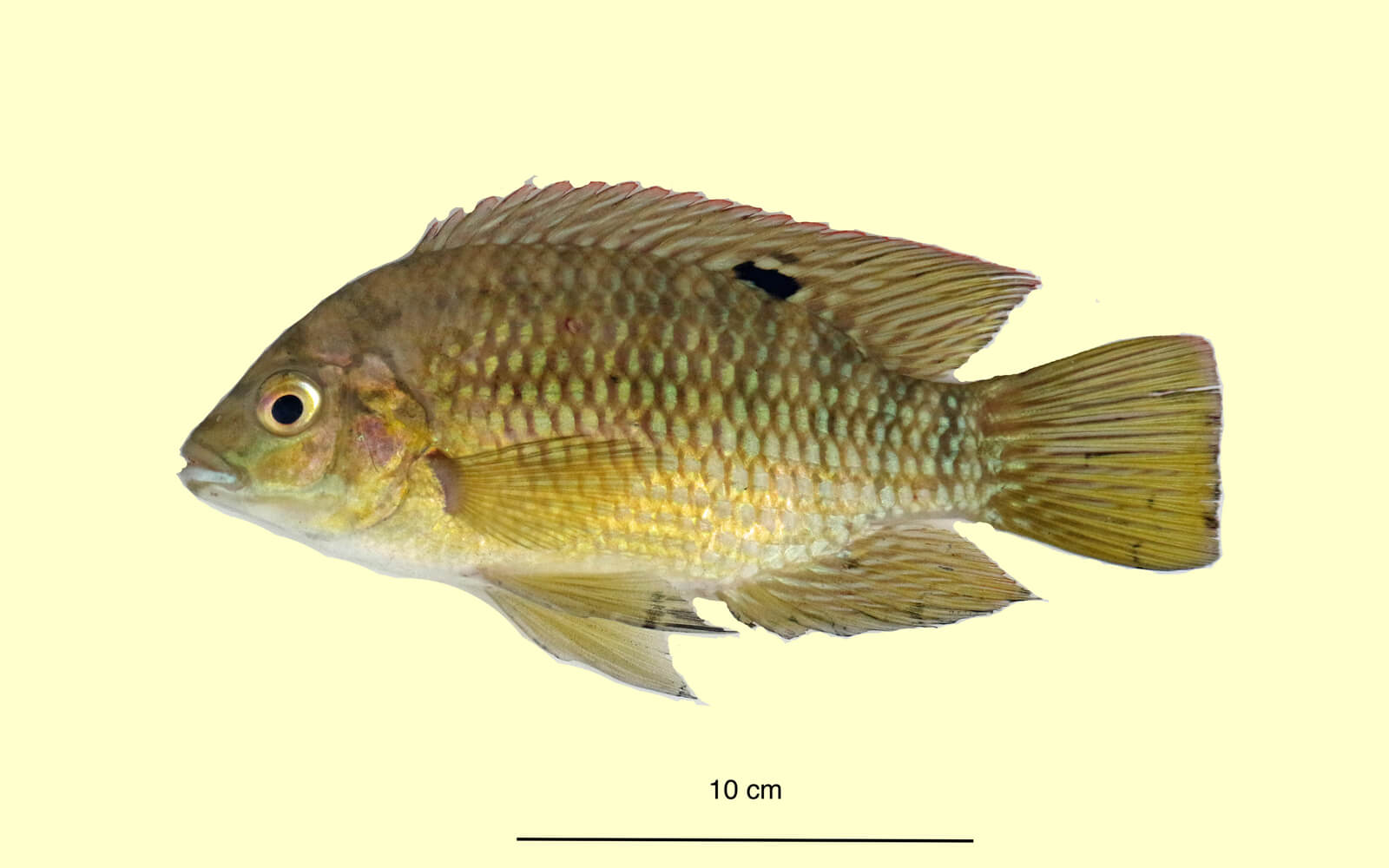

Banded Tilapia

11. Swordtail Xiphophorus helleri

Regarded as “alien invasive” in southern Africa.

This species belongs to a group of freshwater fishes (sub-family Poeciliinae) that are referred to as livebearers because they release live embryos instead of eggs. They are native to America and are popular with freshwater aquarists, particularly novices, because their offspring tend to be hardy and have a high survival rate. A negative consequence is that any release (accidental or intentional) into natural waters will carry an increased risk of invasion. This may have negative effects on the indigenous fish if they prey on their larvae or out-compete them for food. Fortunately most livebearers are dependent on warm waters for survival so their capacity to invade broadly is, to some extent, naturally restricted.

Mature male Swordtail. Females lack the tail extension.

While the primary focus of this survey has been on fish, catches were also made of six large crustacean species. It must be stressed that these records are incidental and should not be seen to comprise a comprehensive checklist or serve as indications of abundances. Five of the species are listed by the IUCN as being of “least concern” while sixth (Caridina africana) is still categorised as “data deficient”.

12. Freshwater Shrimps (family Atyidae)

Most members of this large family of shrimps inhabit fresh water. However a few can tolerate brackish or marine conditions and may even require saline conditions during certain phases of their life cycle. Four species of Atyid shrimps were encountered in our survey. Three of these belong to the Genus Caridina (notably africana, nilotica and typus), while the fourth was Atyoida serrata, a larger, and enigmatic creature, whose presence in Krantzkloof raises some interesting questions.

Caridina are small (around 10 to 30 mm), widespread and often abundant. We observed them at all nine sites. They evidently serve as a significant source of nourishment for higher predators. Their taxonomy is confusing, ill defined and in need of revision. Consequently, we made no attempt at a comprehensive analysis and simply record here that they were universally present and included at least three species. They are poor subjects for photography and this was not attempted.

Atyoida serrata is a rare shrimp that inhabits cascades and fast flowing waters to an altitude of 1200 m. In 2016 the IUCN listed it as a red data species and described it as only being reliably recorded from Madagascar, Comoros, Mauritius and Reunion. Its apparent absence from the African mainland was puzzling. However it appears that they had overlooked a confirmed observation at Splash Rocks in the Molweni River (made by Mike Coke during a National River Health Survey around 2000) and subsequent reports, by him, of their presence in the Uvongo and Mtamvuna rivers on the Kwazulu Natal South Coast. Our survey has revealed their continued presence in the lower Molweni River.

Mature female Atyoida serrata carrying eggs.

Adult male Atyoida serrata.

Atyoida serrata is, in common with other members of the genus, reputed to follow a catadromous life cycle. This entails release of their eggs into the stream and their subsequent dispersal into saline waters for extended larval development. Post-larvae (juveniles) are then thought to actively return to the freshwater environment, which may be within their river of origin or another convenient and suitable river. In this way the survival of the species and its territorial expansion are encouraged. This behaviour is used to explain the wide occurrence of Atyid species at remote island localities across the world’s oceans.

The very restricted distribution of Atyoida serrata on the African continent is curious and raises a number of questions.

Is it perhaps a recently introduced invasive alien species (aquarium escapee)? This seems unlikely. It is not a recognized aquarium subject nor has it shown any evidence of having spread beyond the three localities where it has so far been recorded. The chances of an aquarium release in the largely uninhabited Uvongo and Mtamvuna catchments would also appear to be remote.

Is it perhaps indigenous to South Africa and was simply not detected. Adult Atyoida serrata have a very specific habitat preference, notably cascade sections of rivers close to the coast. Such habitat is not only limited in extent but is often difficult to sample. We suggest that earlier surveys, which mostly relied on hand netting, rather than more effective electrofishing, simply did not observe any. This raises the question of whether there are populations in other rivers along the South African East Coast. We have made a start in answering this question through a wider sampling plan.

There has been a recent upsurge in interest in the taxonomy and distribution of Atyid shrimps, worldwide. In February 2018 Dr. Gerard Marquet, a leading authority on Atyid shrimps, who is based at the French Museum of Natural History in Paris, joined forces with scientists from the Albany Museum in Grahamstown for a survey of rivers between Grahamstown and Durban.

We hosted their visit to Krantzkloof and were able to locate specimens of Atyoida serrata at Splash Rocks. Several were taken to boost the limited numbers currently held in museum collections while others were preserved for DNA barcoding. The latter will hopefully unravel some of the bio-geographical mysteries surrounding its widespread distribution across the western Indian Ocean.

A key question, from our perspective, is whether the South African population is self-contained or dependent on continual recruitment of larvae derived from the Madagascar stocks. The outcome of the DNA barcoding analysis should throw some light on the matter.

A newly discovered ocean current, which links the coastal waters of Madagascar and South East Africa, seems likely to be the conduit for larval transport between the two landmasses. This significant current, which has only recently been uncovered and described (Ramanantsoa et al., 2018), has been named the South-west Madagascar Coastal Current. The authors remark that “its existence is likely to influence local fisheries and larval transport patterns”.

13. Scaly-armed River Prawn Macrobrachium lepidactylus

This species is widespread in Eastern Africa (Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, South Africa), and is also known from Madagascar and Reunion. The males possess enlarged chelae, which are used in vital social interactions such as territorial defense and courtship display. We found them in the Lower Molweni River towards the Umgeni confluence.

Male Scaly-armed River Prawn

14. Natal River Crab Potamonautes sidneyi

These crabs are widespread and common in boulder-strewn streams and rivers across much of Kwazulu Natal. They commonly shelter in burrows that they excavate on muddy riverbanks or under rocks. They come out of their shelters at night, or after rain, and can migrate for significant distances overland under moist conditions. They play an important role in recycling food resources within the river ecosystem and serve as food for higher predators such as Cape clawless otters and water mongooses. Crab remains are often seen in predator scats within Krantzkloof. Few crabs were seen in our survey. However, in view of their secretive and nocturnal habits this is not surprising.

Adult Natal River Crab

Concluding remarks

This survey has revealed a diverse fish fauna, and an abundance of large crustaceans, in the Krantzkloof catchment. This suggests that the watercourses are currently in good ecological health. Two “alien invasive” species (Largemouth Bass and Swordtails) were encountered but provided no evidence of current rampant invasive spread. The information presented here may prove useful in formulating conservation measures and provides a baseline for future monitoring.

Of particular interest and concern, going forward, is the status of Atyoida serrata. The recent (2018) Albany Museum survey found no specimens at the Uvongo and Mtamvuna sites where they were recorded two decades ago. On available evidence, and pending wider and more intense sampling, it appears that Krantzkloof Nature Reserve might currently support the only population of Atyoida serrata on the African continent. While we anticipate that further populations will become evident, this remains to be seen.

References

Chase, F.A. 1983. The Atya-like shrimps of the Indo-Pacific Region (Decapoda Atyidae) Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology (384) Smithsonian Institute Press. 54 pp.

Coke, M. 2018. First records of Atyoida serrata (C.S. Bate) from South Africa (Crustacea: Caridea: Atyidae). African Journal of Aquatic Science 43(2). [in press]

Griffiths, C., J Day and M Picker. 2015. Freshwater Life – A field guide to the plants and animals of southern Africa. Struik Nature. Cape Town. 368 pp.

IUCN 2016. The IUCN Red Data List of Threatened Species. Version 2016-3. http://www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 26 April 2017.

McClurg, T.P and McClurg, N.C. 2018. Report on a survey of fishes and large aquatic invertebrates inhabiting streams and rivers flowing through Krantzkloof Nature Reserve in Kwazulu Natal. Unpublished Report lodged with Kloof Conservancy.

Skelton, P. 2001. A complete guide to the freshwater fishes of Southern Africa. Struik Nature. Cape Town. 395 pp.

Ramanantsoa, J. D., Penven, P.,Krug, M., Gula, J. and Rouault, M. 2018. Uncovering a new current: The Southwest MAdagascar Coastal Current (SMACC). Geophysical Research Letters, 45 https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL075900

South African Department of Water Affairs. South African River Health Programme. State of the Rivers Report. 2002. uMngeni River and Neighbouring Rivers and Streams.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife for permitting us to sample in Kwazulu Natal waterways, Paolo Candotti (Chairman of Kloof Conservancy) for his enthusiastic support, and Mike Coke (editor of the African Journal of Aquatic Science) for his constructive collaboration and for reviewing the manuscript.

About the author

Tim McClurg B. Sc. Hons. (Cape Town), M. Sc. (UKZN), Pr. Sci. Nat. specialises in ecological impact assessment with a particular emphasis on the marine and estuarine environments. He is semi-retired and lives on the edge of Krantzkloof. Cell 083 7901356.

About the author

Nick McClurg Dip. Agric. (Cedara), B.Tech. (DUT) specializes in assessing environmental impacts in freshwater habitats using invertebrate and fish community structure as proxy measures of stress. Cell 073 2331904.