Small though they are, insects seem to excel at everything. They have the five senses that we do, and then some. They hear, taste, smell, see and feel. But that’s not all!

Vinegar flies have speedometers and gravity meters. Bogong moths complete long night-time migrations navigating by stars and the magnetic field of the earth. Bees can see ultraviolet light. Some flowers wanting to attract their insect pollinators, or butterflies wanting to attract a mate, display special patterns that are only visible in ultraviolet light.

Insects have different types of eyes. The biggest and most obvious are the compound eyes. Compound eyes have tiny lenses (‘ommatidia’). Each lens sends its own light spot signal to the brain. The brain converts the signals into one large pixelated image. The more ommatidia the eye contains, the more detailed the image becomes.

Nearly the entire head of this drone fly is covered in eye.

Zooming in on the eye, you can make out thousands of tiny ommatidia.

The compound eyes dragonflies have up to 30 000 ommatidia, house flies have 4000, some ants have less than ten.

Simple eyes (‘ocelli’) do not form an image. They detect light intensity. Gradual changes in light helps insects tell the time – both hours and seasons.

The arrows point to the ocelli. In this flower mantis the ocelli have pink and yellow coloured fish-eye lenses. One can only guess what kind of visual cues they pick up with those sensitive light detectors.

Don’t be fooled! Not everything that looks like an eye can see.

Those eye spots are not eyes at all. They are coloured markings that disguise the caterpillar as a snake to scare off predators.

The black spots on this venomous stinging slug moth caterpillar are not eyes either. Those are black hairs the caterpillar displays when frightened.

Not even these are eyes! What looks like large head-hugging compound eyes in this chap is just the hard, black head capsule.

Caterpillars only have a few light-sensitive spots or ocelli.

(By the way, those red whips on the swallowtail caterpillar above, are not feelers. When threatened, the caterpillar rears up and extends a glandular sac that looks like a snake’s forked tongue and produces a repellent chemical.)

Stylopids (order Strepsiptera) are strange insects with many weird and unique features. They parasitise other insects. The males have amazing eyes in which each ommatidium has its own full retina that forms its own complete picture, not just a spot of light. As a result, stylopids see the world as a jigsaw puzzle, made up of multiple detailed pieces, and not just a pixelated picture composed of light dots.

Male stylopid

Photo: Mike Quinn

Many insects (those that communicate using sound) have proper ears. Except the ears are not quite in the same place as ours.

Katydids’ ears are on their front knees.

In grasshoppers and cicadas the ear drums, or ‘tympana’, are on the thorax.

Beautifully camouflaged grasshopper. The arrow points out the ear drum.

Even insects without proper ears can sense vibrations in the air, water or ground, with the help of tiny sensory hairs that cover most of their body. These hairs, called ‘setae’, are also sensitive to touch and can even detect wind speed and humidity.

Insects don’t have a nose to smell with. They don’t even have noses! They don’t breathe through their head, but through holes on their body.

Insects ‘smell’ or ‘taste’ chemicals using sensory hairs, or ‘sensilla’, that grow on various body parts, for example, on their feet.

House flies ‘taste’ the food while walking over it.

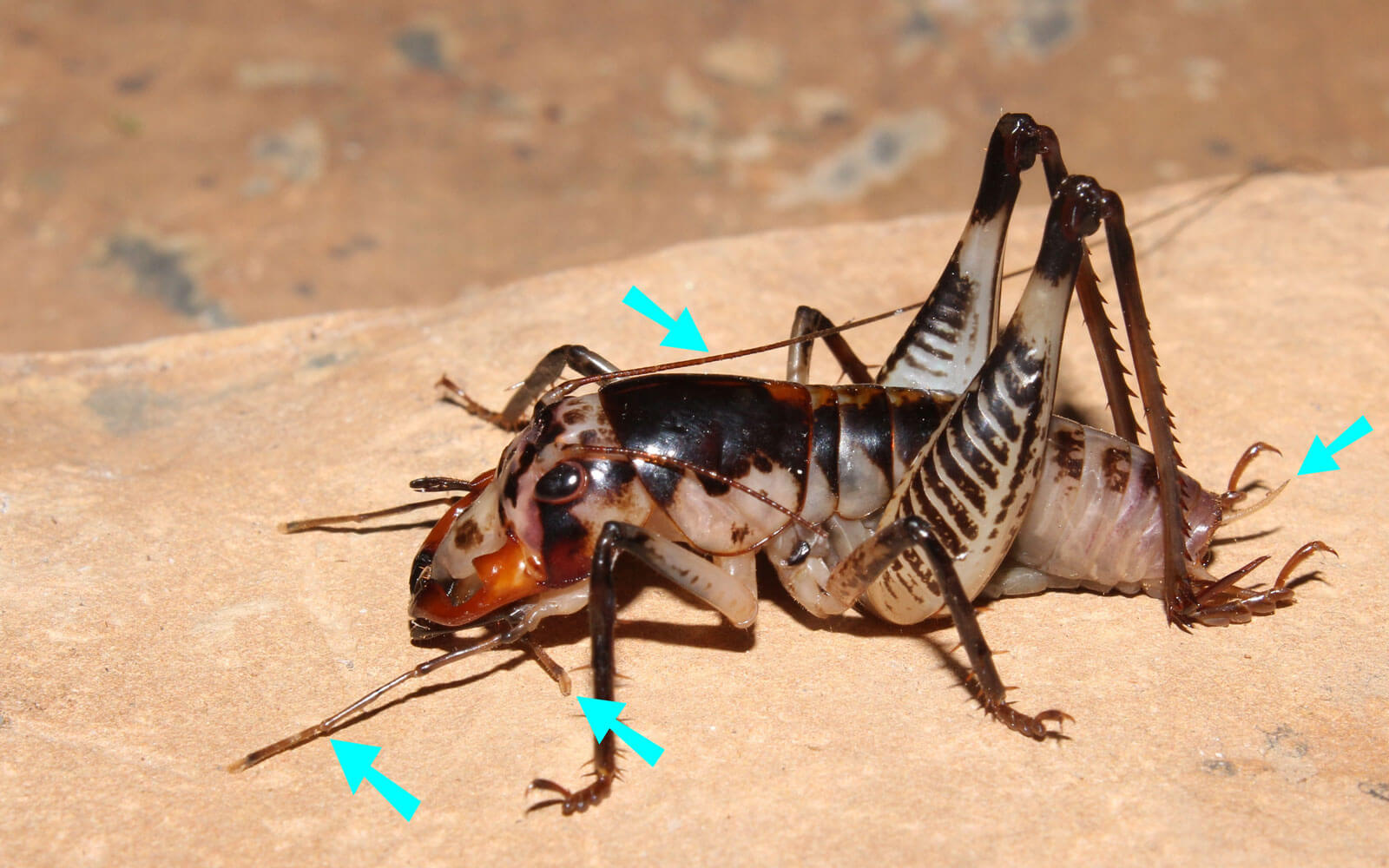

Insects’ main sensory organs are of course their various feelers – see blue arrows in the picture below. There are one pair of head feelers (‘antennae’), two pairs of mouth feelers (‘maxillary palps’ and ‘labial palps’), and one pair of rear-end feelers (‘cerci’ – remember those from the last article?).

This weird king cricket, with enormous jaws, has particularly long mouth feelers. The close-up from underneath shows how the maxillary and labial palps are attached to the head.

Feelers, which are covered with both setae and sensilla, come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. The larger the surface area, the more sensitive they are. Some male moths can smell a female from over 10km away!

Many moths, like this amazing Atlas moth, have dramatic fan-shaped or feathery feelers.

In this large click beetle the antennae are made up of flat plates that open and close like a book.

This longhorn beetle has feelers that are twice as long as its entire body.

Sometimes I wonder how the insects cope in this world that humans have altered so fundamentally. Atmosphere, ground and water is infused with toxic chemicals, the air vibrates with strange radio waves and electric charges, nights are no longer dark, lit up by innumerable artificial suns and stars. So how do they cope? Not well it seems. Not well at all.

Today I leave you on a grave note. I am sad and worried about the state of nature. We humans seem to have “eyes to see but do not see and ears to hear but do not hear”. Nature is crying out, creation is falling apart around us. Are we going to take note? Are we going to listen? Are we going to change our ways?

About the author

Marlies Craig is an epidemiologist who used to research malaria, but now works for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Though she did originally study Biology and Entomology, her love affair with insects is very personal. In her book What Insect Are You? – Entomology for Everyone, she shares that passion with young and old. She hopes to kindle in children a deeper appreciation and understanding of nature and show them why and how they can make a difference. Find Marlies’s website at What Insect Are You?.